Twenty twenty was an unpleasant year for so many reasons. It was a year of riots, unemployment, and the trend in overall rising mortality continued unabated.

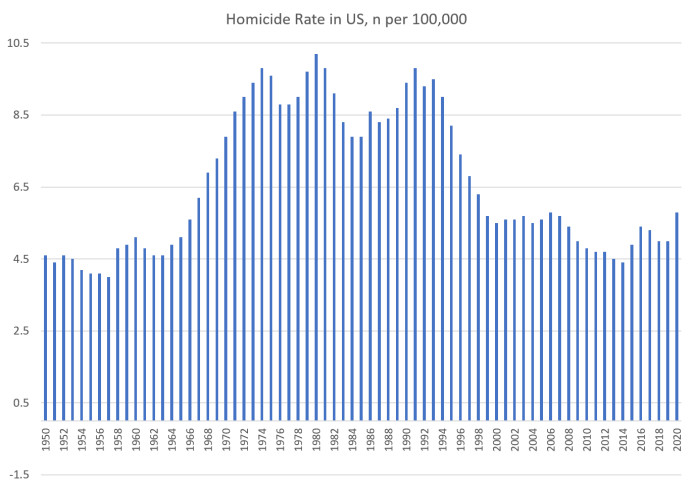

Homicides also increased.

In fact, in preliminary homicide data, it looks like homicides increased a lot in 2020.

According to the FBI’s Preliminary Uniform Crime Report for the first half of 2020, “murder and nonnegligent manslaughter offenses increased 14.8%, and aggravated assault offenses were up 4.6%.”

If the second half of 2020 proves to be about the same as the first half, then the nationwide homicide rate for 2020 will have risen from 5 per 100,000 in 2019 to 5.8 per 100,000 in 2020. That’s a big increase, and puts 2020’s total at the highest rate recorded in fifteen years, matching 2006’s rate of 5.8 per 100,000.

Some other data, however, suggests the year-end numbers for 2020 will be even worse than that. Homicides look to be up more than 20 percent during the fall of 2020 compared to the previous year. Thus, the increase from 2019 to 2020 may prove to be one of the largest increases in homicide in more than fifty years.

Source: FBI, “Crime in the US” report, 2020 preliminary report.

Meanwhile, homicides in certain cities increased by far worse rates. Year-over-year increases of 30 percent or more were common in 2020, and this wasn’t limited to only large cities.

In data posted by researcher Jeff Asher, total year-over-year homicides through September 2020 were up in a wide range of locations: up 55 percent in Chicago, up 54 percent in Boston, up 38 percent in Denver, and up 105 percent in Omaha.

What Caused the Surge?

It’s much easier to count homicides than to determine the events and phenomena driving trends in homicides. It’s never a good idea to attribute changes in homicide totals to any single cause.

Nonetheless, we can hazard some guesses.

If we’re going to ask ourselves what might have caused such an unusually large rise in homicide, we ought to look for unusual events.

Most obvious among these, of course, are the stay-at-home orders, business closures, and lockdowns that have occurred since March of last year. These are pretty unusual things.

Although it is considered somewhat heretical to point out that lockdowns can produce negative societal side effects, the connection to violent behavior is so undeniable that this is now openly admitted.

For example, in a recent interview with The Atlantic, sociologist Patrick Sharkey discusses some of the likely causes of 2020’s surge in violence, stating:

Last year, everyday patterns of life broke down. Schools shut down. Young people were on their own. There was a widespread sense of a crisis and a surge in gun ownership. People stopped making their way to institutions that they know and where they spend their time. That type of destabilization is what creates the conditions for violence to emerge.

When asked if “idle time” caused by lockdowns was somehow connected to rising homicides, Sharkey continued:

It’s not just idle time but disconnection. That might be the better way to talk about it. People lost connections to institutions of community life, which include school, summer jobs programs, pools, and libraries. Those are the institutions that create connections between members of communities, especially for young people. When individuals are not connected to those institutions, then they’re out in public spaces, often without adults present. And while that dynamic doesn’t always lead to a rise in violence, it can.

The connection between a lack of community institutions and social dysfunction is well known by sociologists.1

Last year, when looking at the role the stay-at-home orders might have had on the summer’s riots, I wrote:

As much as lockdown advocates may wish that human beings could be reduced to creatures that do nothing more than work all day and watch television all night, the fact is that no society can long endure such conditions.

Human beings need what are known as “third places.” …

As described by a Brookings Institution report, these third places include churches, parks, recreation centers, hairdressers’ shops, gyms, and even fast-food restaurants.

Yet, the lockdown advocates, in a matter of a few days, cut people off from their third places and insisted, in many cases, that this would be the “new normal” for a year or more.

These third places cannot simply be shut down—and the public told to just forget about them indefinitely—without creating the potential for violence and other antisocial behavior.2

Few of these places exist for the explicit purpose of reducing violence, although they tend to have this effect. But during the government-mandated lockdowns, some organizations specifically devoted to violence prevention were shut down and, as noted by law professor Tracey Meares, the pandemic has prevented many antiviolence programs from operating. These programs, however, require “a great deal of a face-to-face contact, typically, among service providers and the folks who are most likely to both commit these offenses and be the victims of them,” Meares says. “And it’s a lot harder to do that when people can’t meet in person.”

Of course, it’s not that these people just can’t meet in person, as if it were physically impossible to do so. It’s that in many places they are legally prohibited from doing so. This means even the most urgent cases were neglected and put on the back burner because policymakers made a decision to ignore the realities of violent crime in order to obsess over covid risks.

And this is a point that must be made repeatedly. “The pandemic” isn’t what caused the widespread destruction of social institutions that are key in increasing social cohesion and preventing violence. Government edicts did this. Certainly, given fears over covid infection, it stands to reason that many people would have elected to stay home, and that important social institutions would have functioned at reduced capacity even without government mandates.

However, what government mandates did was prevent people from even using their own discretion, which means even the most at-risk, isolated, and emotionally volatile people—the people who need these institutions the most—were cut off from important resources.

Also important in understanding homicides is the fact covid lockdowns have increased domestic violence; as Sharkey notes, “Intimate-partner violence increased in 2020.”Again, advocates for stay-at-home orders have used their bizarrely extreme preoccupation with covid deaths as an excuse to insist it is “worth it” to keep women and children locked up with their abusers. Homicides have increased as a result in many cases.

The Role of Police in Lockdown Enforcement

The lockdowns aren’t the only factors behind rising crime, of course. Another factor in the rising homicide rate is likely the decline of the public’s trust in police institutions.

The reputations of police and police organizations appear to have gone into significant decline in recent years as police encounters are increasingly being recorded and made public—thus exposing police abuse and what at least appears to be police abuse.

These events have been connected to rising rates of violent crime.3 As noted by both Sharkey and by crime historian Randolph Roth, the public’s trust in government institutions—which certainly includes police—can impact a community’s willingness to turn to violence in personal interactions.

In other words, antipolice sentiment is regarded as a likely indirect cause of growing homicide rates. This declining trust manifested itself in last summer’s riots, but the origins of the riots predate both the riots and the George Floyd case.

But even when we look to the role of police agencies’ status within communities, we find that the stay-at-home orders and lockdowns again play a role.

It is the police, after all, who have been responsible for enforcing government orders to wear masks, close businesses, and avoid gatherings. Throughout 2020, police have been a central in harassing churchgoers, beating up nonviolent citizens for not “social distancing,” and arresting women for not wearing masks. Police have also arrested business owners and shut down their businesses. And then there was the case of a six-year-old girl who was taken from her mother because the mother wasn’t wearing a mask when she dropped her daughter off at school. Who will be providing the regime’s muscle when it comes to separating this child from her mother? Naturally, it will be the police.

Although the police have continued to enjoy uncritical support from the “Back the Blue” movement, more reasonable people can only tolerate so much when it comes to police who willingly attack and arrest people for the noncrimes of using their own private property or not wearing a mask on a public sidewalk.

Reversing the Damage Done in 2020

It’s unclear at this point if reversing policies that caused a year of community destruction can quickly undo the damage. In any case, however, the responsible thing to do is end any and all policies that keep churches, community centers, and meeting spaces closed. The police must be out of the business of roughing people up in the name of social distancing. The politicians’ obsession with isolating people must end.

- 1. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg discusses this in his influential 1989 book The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community.

- 2. Sharkey also notes what is well known to criminologists but not well known by the general public: that economic recessions do not necessarily or generally lead to increases in violent crime.

- 3. See Tanaya Devi and Roland G. Fryer Jr., “Policing the Police: The Impact of ‘Pattern-or-Practice’ Investigations on Crime” (NBER Working Paper 27324, June 2020).