Traditionally, Austrian theorists have focused with particular interest on the recurrent cycles of boom and recession that affect our economies and on studying the relationship between these cycles and certain characteristic modifications to the structure of capital-goods stages. Without a doubt, the Austrian theory of economic cycles is one of the most significant and sophisticated analytical contributions of the Austrian School. Its members have managed to explain how credit-expansion processes lead to systematic investment errors that result in an unsustainable productive structure. Such processes are advanced and orchestrated by central banks and implemented by the private-banking sector, which operates with a fractional reserve and creates money from nothing in the form of deposits, which it injects into the system via loans to companies and economic agents in the absence of a prior real increase in voluntary saving. The productive structure shifts artificially toward numerous projects which are too capital intensive and could mature only in a more distant future. Unfortunately, economic agents will be unable to complete these projects, because they are not willing to back them by sacrificing enough of their immediate consumption (in other words, by saving). Certain reversion processes inevitably follow and reveal the investment errors committed, along with the need to acknowledge them, abandon unsustainable projects, and restructure the economy by transferring productive factors (capital goods and labor) on a massive scale from where they were used in error to new, less ambitious but truly profitable projects. The recurrence of the cycle can be explained both by the essentially unstable nature of fractional-reserve banking as the main provider of money in the form of credit expansion and by the widespread inflationary bias of theorists, political authorities, economic and social agents, and above all, central bankers, who view economic prosperity as a goal to be pursued in the short term at all costs and see monetary and credit injections as a tool which cannot, under any circumstances, be dispensed with. Therefore, once recovery is well underway, sooner or later the authorities again succumb to old temptations, rationalize policies that have failed again and again, and reinitiate the whole process of expansion, crisis, and recession, and it all begins again.

Austrian economists have proposed the reforms necessary to end recurring cycles (basically, the elimination of central banks, the reprivatization of money – the classic pure gold standard – and making private banking subject to the general principles of private property law – that is, a 100-percent reserve requirement for demand deposits and equivalents). However, Austrians have always stipulated that these reforms would not avert isolated, non-recurring economic crises if, for instance, wars, serious political and social upheaval, natural catastrophes, or pandemics cause a large increase in uncertainty, sudden changes in the demand for money and, possibly, in the social rate of time preference. In such cases, the productive structure of capital-goods stages might even be permanently altered.

In this paper, we will analyze the extent to which a pandemic like the current one (and similar pandemics have struck a great many times in the history of mankind) can trigger these and other economic effects and the extent to which states’ coercive intervention can mitigate the negative effects of pandemics or, on the contrary, can become counterproductive, aggravate these effects, and make them last longer. First, we will study the possible impact of the pandemic on the economic structure. Second, we will consider the functioning of the spontaneous market order driven by the dynamic efficiency of free and creative entrepreneurship. In this scenario, entrepreneurs devote their attention, in a decentralized manner, to detecting the problems and challenges a pandemic poses. In contrast, we will analyze the impossibility of economic calculation and of the efficient allocation of resources when political attempts are made to impose decisions from above; that is, in a centralized way, using the systematic, coercive power of the state. In the third and final section of this paper, we will examine the specific case of massive intervention by governments and, especially, central banks in monetary and financial markets to deal with the pandemic by seeking to lessen its effects. We will focus also on simultaneous government policies involving taxes and an increase in public spending which are presented as the panacea and universal remedy for the evils that afflict us.

1. The Effects of Pandemics on the Real Productive Structure: The Labor Market, the Process of Capital-Goods Stages, and the Impact of Uncertainty

1.1. The Labor Market

The emergence of a new, highly contagious illness which spreads throughout the world and has a high mortality rate constitutes, without a doubt, a catastrophic scenario capable of producing a number of serious economic consequences in the short, medium, and even long term. Among these is the cost in terms of human lives, many of them still actively productive and creative. Let us recall, for instance, that the so-called “Spanish flu” killed an estimated 40 to 50 million people worldwide beginning in 1918 (over three times the number of dead, including both combatants and civilians, in World War I). This flu pandemic attacked mainly men and women who were relatively young and strong; that is, people of prime working age.1 In contrast, the current Covid-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus produces comparatively mild symptoms in 85 percent of those infected, though it hits the remaining 15 percent hard. It requires even hospitalization for one-third of these and leads to the death of close to one in five of those hospitalized with a severe case of the disease, the vast majority of whom are elderly, retired people and people with serious pre-existing conditions.

Thus, the current pandemic is not having a noticeable impact on the supply of labor and human talent in the labor market, since the increase in deaths among people of working age is relatively small. As I have already mentioned, this situation differs considerably from the one that arose with the “Spanish flu,” after which it is estimated that the aggregate supply of labor fell worldwide by over 2 percent. This figure takes into account fatalities from both the disease and World War I (40 or 50 million casualties from the disease and over 15 million from the war). This relative shortage of labor pushed up real wages during the Roaring Twenties, when the restructuring of the world economy was completed. It went from a wartime to a peacetime economy, and the whole process was accompanied by great credit expansion, which we cannot analyze in detail here, but which, at any rate, set the stage for the Great Depression that followed the severe 1929 financial crisis.2

Over the course of history, various pandemics have actually exerted a much stronger impact on the labor market. For instance, it is estimated that the Black Death, which ravaged Europe beginning in 1348, reduced the total population by at least one third. The acute, unexpected shortage of labor that resulted led to considerable real-wage growth, which took hold in subsequent decades. It is exasperating that monetarists and, particularly, Keynesians tiresomely go on about what they suppose to be the “beneficial” economic effects of wars and pandemics (for everyone except the millions who are killed or impoverished by them, I imagine). It is argued that these tragedies permit economies to overcome their lethargy and start on the road to a buoyant “prosperity.” At the same time, such calamities provide justification for economic policies of intense monetary and fiscal interventionism. With his customary insight, Mises refers to these economic theories and policies as pure “economic destructionism,” since they simply serve to increase the money supply per capita along with, and especially, government spending.3

1.2. The Productive Structure and Capital Goods

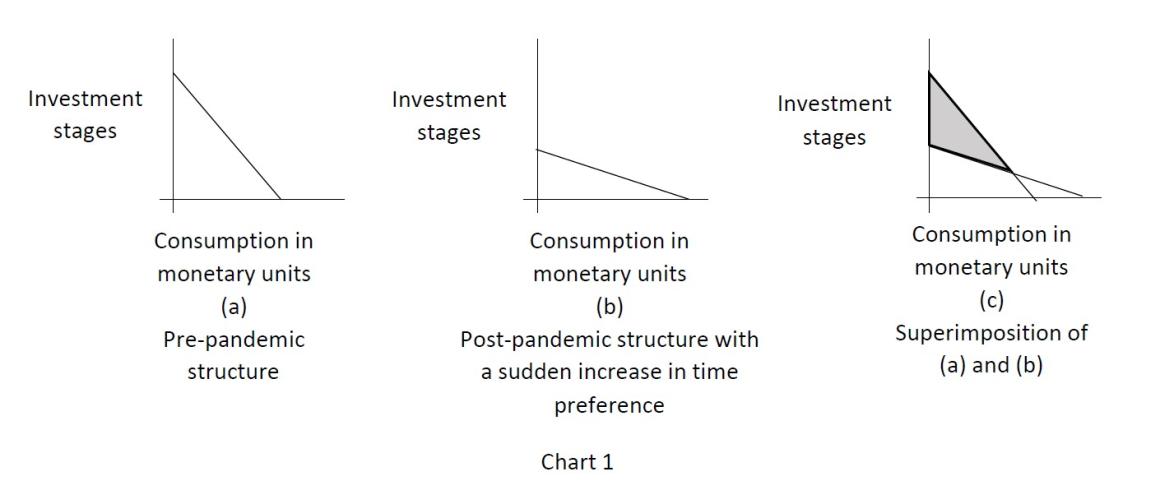

Aside from these effects on the population and the labor market, we should also consider the impact a pandemic exerts on the social rate of time preference and hence, on the interest rate and the productive structure of capital-goods stages. Perhaps the most catastrophic scenario conceivable is the one Boccaccio describes in his introduction to the Decameron when he writes of the bubonic plague that afflicted Europe in the fourteenth century. For if the belief becomes widespread that everyone is very likely to catch a disease and die in the short or medium term, it is quite understandable that subjective valuations become geared toward the present and immediate consumption. “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” Or conversely, “Let us repent, do penance, pray, and get our spiritual lives in order.” These two opposing and yet perfectly comprehensible attitudes toward the pandemic have the same economic effect: What sense is there in saving and launching investment projects that could mature only in the distant future if neither we nor our children will be here to enjoy the fruits of them? The obvious result could be seen in fourteenth-century Florence, ravaged by the bubonic plague. En masse, people abandoned farms, livestock, fields, and workshops and, in general, they neglected and consumed capital goods without replacing them.4 This phenomenon can be illustrated graphically in a simplified fashion as described in the section “The Case of an Economy in Regression” of my book Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles.5 There, I use the well-known Hayekian triangle, which represents the productive structure of a society. (For a detailed explanation of its meaning, see pages 291 and following of the book.)

As we see in Chart 1, in this case a sudden, dramatic increase in the social rate of time preference augments immediate monetary consumption (figure b) at the expense of investment. Specifically, numerous stages (represented by the shadowed area in figure c) in the production process are abandoned, a very large portion of the population stops working (either because of death or voluntarily), and the survivors earnestly devote themselves to consuming consumer goods (the prices of which, in monetary units, skyrocket due to the reduction in their supply and the widespread decrease in the demand for money). Transactions in the time market and loanable funds practically come to a halt, and interest rates on the few that do take place go through the roof.

In contrast to the above scenario, there is no indication that the current Covid-19 pandemic has been accompanied by a significant change in the social rate of time preference (aside from the effect of a temporary increase in uncertainty, which we will discuss later). To begin with, the current circumstances in no way resemble those of a pandemic as virulent as the one Boccaccio describes in the Decameron. As I have pointed out, the expected mortality among people of working age is virtually negligible, and expectations regarding the successful completion of investment processes that will mature in the distant future remain unchanged. (For instance, investments are still being made in the design, innovation, and production of the electric cars of the future and in many other long-term investment projects.) And since the social rate of time preference remains basically unchanged, the productive structure of capital-goods stages described in a simplified manner in our Hayekian chart also remains unchanged, except for three effects – one in the immediate short term, another in the medium term (one to three years), and another in the long term (which may become indefinite).

1. First, there is the immediate, short-term effect (lasting a few months) exerted on the real productive structure by the coercive confinement measures governments have imposed. We can assume that the economic standstill decreed for several months has, in relative terms, affected mainly those productive efforts furthest from final consumption. After all, the population – even people confined to their homes and unable to work – have had to go on demanding and consuming consumer goods and services (even if through e-commerce – Amazon, etc. – since many stores and final distributors were forced to close, because their activities were considered “non-essential”). If this is so, and assuming the final demand for money intended for consumption has not significantly changed, either because households on government-imposed lockdown have dipped into their financial reserves or because they have made up for their decrease in income by relying on temporary unemployment subsidies (lay-off compensation, etc.), the productive structure in monetary terms will have fluctuated over a short interval like a pendulum, as shown below (in Chart 2).

At any rate, when the compulsory “disconnection” from the production process ends and productive factors are again employed, the production process can start again where it left off, since no systematic, malinvestment-causing errors requiring restructuring have come to light.6 Unlike what happened in the Great Recession of 2008, the productive structure has not been irreversibly harmed, and thus there is no need for a prolonged, painful process of reorganization and massive reallocation of labor and productive factors: All that is needed is for entrepreneurs, workers, and self-employed people to go back to work, pick up their tasks where they left off, and use the capital equipment that was not damaged (several months ago) and is still available now.

Concerning this first effect in the immediate short term, I should clarify that it would also have appeared – though it would have been much gentler and less traumatic and, thus, would have caused a much smaller fluctuation than the pendular movement reflected in the chart – if confinement had been voluntary and selective and the decision had been made on the “micro” level by families, companies, residential areas, neighborhoods, etc. in the context of a free society in which either no monopolistic governments exist (and instead we have the self-rule of anarcho-capitalism) or they are not centralist and do not impose widespread, coercive, and indiscriminate confinement measures.

2. Second, various sectors fundamentally associated with the stage of final consumption are still experiencing a dramatic decrease in demand after the confinement and may continue to do so for many months7 until the pandemic has ended and activities have completely returned to normal. These sectors deal primarily with tourism, transportation, the hotel industry, and entertainment, and relatively speaking, they are very important to certain economies like that of Spain, where tourism accounts for almost 15 percent of GDP. Such sectors require a more profound change than the mere pendular fluctuation described in the first point above. Instead, circumstances necessitate a change which has an impact on the productive structure for a longer period of time (around two years). Obviously, other things being equal, if households spend less on air transportation, hotels, restaurants, and theater performances, they will spend more on alternative consumer goods and services, or substitutes, they will devote more of their income to investment, or they will increase their cash balances. Aside from a possible increase in the demand for money, which we will discuss later when we consider uncertainty, clearly the productive structure will have to adapt temporarily to the new circumstances by making the most of the active resources remaining in the sectors (at least partially) affected. I am referring particularly to those resources that are, for a time, involuntarily unemployed and will have to be reallocated to alternative lines of production where they can find fruitful (temporary or definitive) employment.

As an illustration, certain restaurants will stay open against all odds by adapting their offerings (for instance, preparing meals for home delivery), reducing costs as much as possible (laying off personnel or retraining them directly or indirectly – for example, to be delivery people), and adjusting their liabilities to suppliers in order to minimize losses and capital consumption. In this way, the owners avoid having to throw away years invested in building a reputation and accumulating highly valuable capital equipment that is difficult to repurpose. And they hope that, when circumstances change, they will be better positioned than their competitors and have a great competitive advantage when coping with the renewed recovery that is expected for the sector. In contrast, other entrepreneurs will choose to withdraw and “hibernate” by temporarily closing their doors but leaving the corresponding facilities and business contacts prepared for a reopening as soon as circumstances permit. Yet another group of business people – generally those whose entrepreneurial projects were marginally less profitable even under pre-pandemic conditions – will be forced to permanently shut down their businesses and liquidate their respective entrepreneurial projects.

All of these entrepreneurial activities and decisions can and must take place relatively quickly, and costs must be minimized. This will be possible only in a dynamically efficient economy which encourages the free exercise of entrepreneurship and does not obstruct it with harmful regulations (especially in the labor market) and discouraging taxes. Clearly, it will not be the government or public officials who will manage to make the most appropriate decisions at every moment and in each set of specific circumstances of time and place. Instead, it will simply be an army of entrepreneurs who, in spite of all adversity, wish to move forward and, with fortitude and unshakeable trust in a better future, remain confident that sooner or later it will arrive.

Regarding the triangle we use to represent, in a simplified way, the productive structure, the most we can depict (see Chart 3), assuming no significant change in the social rate of time preference occurs, is a horizontal fluctuation of the hypotenuse, first to the left, which shows the overall impact of the decrease in demand experienced in the affected sectors (and by suppliers in those sectors), and then back to the right, as it is replaced by new demand over the period of months it takes for complete normalcy to return, and to the extent that most of the money demand lost in those sectors is recovered.

Obviously, the chart does not permit us to show the countless entrepreneurial decisions and real investment transactions that result in the rapid and flexible horizontal fluctuation represented by the two-way arrows. The chart does, however, permit us to visualize the grave risk involved in launching policies that tend to make the productive structure more rigid by maintaining zombie companies that should be liquidated as soon as possible and by making it more difficult, via regulations and taxes, for a rebound to occur and push the hypotenuse of our triangle back to the right. In fact, fiscal and regulatory intervention can fix the real productive structure in the BB position indefinitely and prevent it from rebounding toward the AA position.

It goes without saying that all of these rapid-adjustment and recovery processes require a highly agile and flexible labor market in which it is possible to lay off and rehire personnel very quickly and at minimal cost. We must remember that unlike what happened in the Great Recession of 2008 (and happens in general after any financial crisis that follows a lengthy process of credit expansion), in the current pandemic we are not starting from a widespread malinvestment of productive factors (in the building sector, for instance, as occurred in 2008) which could justify a large volume of long-term structural unemployment. Instead, it is possible now to reallocate labor and productive factors in a quick, sustainable, and permanent way, but the corresponding labor and factor markets must be as free and agile as possible.

3. Third, we have yet to analyze the possibility that certain changes in the consumption habits of the population may occur, become permanent, and require permanent modifications to society’s productive structure of stages of investment in capital goods. We should point out that in any uncontrolled market economy, the productive structure is always adapting in a gradual, non-traumatic way to changes in consumers’ tastes and needs. It is true that the pandemic may hasten most consumers’ discovery and definitive adoption of certain new behavioral habits (pertaining, for instance, to widespread participation in e-commerce, the increased use of certain payment methods, and the mainstreaming of video conferences in the world of business and education, etc.). However, in practice we may be exaggerating the impact of these supposedly radical changes, especially if we compare them to the changes that have arisen, since the start of the twenty-first century, both from an even greater globalization of trade and exchange and from the technological revolution that has accompanied it and made it possible. These developments have enabled hundreds of millions of people to escape from poverty; billions of people (particularly from Asia and Africa) who until now remained outside the circuits of production and trade distinctive of market economies have been incorporated into the flows of production. Thus, the productive forces of capitalism have been unleashed like never before in the history of mankind. And despite the burden of state intervention and regulation, which continually hinder progress and clip its wings, humanity has achieved the great social and economic success of being 8 billion strong and maintaining a standard of living that only a few decades ago could not even have been imagined.8 From this perspective, we should justly give less importance to the long-term impact of the current pandemic in a context of much bigger and more profound changes to which market economies are constantly adapting without major difficulties. Hence, we should again turn our analysis to the study of the short- and medium-term effects of the current pandemic, since, due to their closer proximity to us, we can regard them as more significant at this time.

1.3 Uncertainty and the Demand for Money

To wrap up the first part of this paper, we will now consider the impact of the uncertainty the pandemic has caused. In taking this approach, my main purpose is to highlight, as we will see in the final part, the fact that this uncertainty has led to even further promotion of fiscal and (especially) monetary intervention policies so extremely lax that they are historically unprecedented, pose a serious threat, and may well continue to have severe consequences once the current pandemic has ended.

Initially, the impact of a pandemic on uncertainty and, thus, on the demand for money can range between two opposing extremes. A pandemic may be so virulent that, as we saw in the case of the bubonic plague in Florence in the mid-fourteenth century, which Boccaccio describes so well in the Decameron, more than uncertainty, it gives a very large swathe of the population the certainty that their days are numbered and that hence, their life expectancy has been drastically reduced. Under such circumstances, it is understandable that the demand for money collapses and money loses much of its purchasing power in a context in which no one wishes to part with goods or provide services whose production has largely nosedived, and most people wish to consume these as soon as possible.

Of more analytical interest to us now are pandemics like the current one, which are far less virulent and in which, though the survival of most of the population is not in danger, uncertainty does escalate, particularly in the early months, with respect to the breadth, evolution, and rate of the spread and its economic and social effects. Cash balances are the quintessential means of dealing with the ineradicable uncertainty of the future, since they permit economic actors and households to keep all of their options open and thus to adapt very quickly and easily to any future situation once it emerges. Therefore, it is understandable that the natural increase in uncertainty stemming from the current pandemic has been accompanied by an increase in the demand for money and thus, other things being equal, in its purchasing power. Chart 4 can help us to visualize this. The chart contains several triangular diagrams which represent the productive structure in terms of the demand for money. These diagrams depict the effect of the increase in the demand for money as: a uniform movement of the hypotenuse to the left when the rate of time preference does not change (diagram a), a movement to the left that reflects greater relative investment when cash balances are accumulated by decreasing consumption (diagram b), and a movement to the left that reflects greater relative consumption when the new money is accumulated by selling capital goods and financial assets but not by reducing consumption (diagram c).

Three possible effects exerted on the productive structure by the increase in the demand for money stemming from the pandemic:

Although any of these three effects is theoretically possible, it is most likely that under the current circumstances there has been a combination of them, particularly of the situations reflected in diagrams a and b. Hence, we could superimpose these diagrams on those we analyzed from the charts in earlier sections. To make those initial charts easier to understand and examine separately, we did not consider the effects of a possible increase in the demand for money, and we are now including this in our analysis. There are three important points to bear in mind concerning the increase in uncertainty and in the demand for money stemming from the pandemic.

First, the increase in uncertainty (and the accompanying increase in the demand for money) is temporary and of relatively short duration, since it will tend to revert as soon as we begin to see the light at the end of the tunnel and expectations of improvement emerge. Therefore, it will not be necessary to wait until we have completely overcome the pandemic (around two years). Before then, there will be a gradual return to “normal” levels of uncertainty; the movements depicted in diagrams a, b, and c, will change direction, and the productive structure in monetary terms will return to its prior state.

Second, as the new money balances accumulate due to the reduction in the demand for consumer goods (diagrams a and b) – and this certainly does occur in the sectors most affected by mobility restrictions (the tourism and hotel industries, etc.) – this lower monetary demand for consumer goods will tend to leave a significant volume of them unsold. As a result, it will be possible to cope with both their production slowdown (which arises from the inevitable bottlenecks and the greater or lesser confinement of their producers) and the demand derived from the need to continue consuming experienced by all of the people who completely or partially stopped working during the early months of the pandemic’s impact. Therefore, the increase in the demand for money serves an important absorber with respect to the supply shock that occurs in the production of consumer goods as a result of the obligatory confinement. Hence, in this way, the relative prices of these goods are kept from skyrocketing, which would seriously harm the broadest sectors of the population.

Third and last, we must point out that monetary, fiscal, and tax interventionism by governments and central banks can increase uncertainty even further and may actually prolong it beyond what is strictly necessary and the pandemic alone would have required. Without a doubt, and as we will see in greater detail in the third section, governments and central banks can create an additional climate of entrepreneurial mistrust which hampers the quick recovery of the market and obstructs the entrepreneurial process of returning to normalcy. It would even be possible in this way to replicate the perverse feedback loop I study closely in my article, “The Japanization of the European Union.”9 In this perverse loop, central banks’ massive injection of money supply and lowering of interest rates to zero produce no noticeable effect on the economy and are self-defeating. This is because they are neutralized by the simultaneous money-demand increase that follows from the zero opportunity cost of holding liquid assets and, especially, from the additional rise in uncertainty caused by the very policies of tighter economic regulation, blocking pending structural reforms, raising taxes, interventionism, and a lack of fiscal and monetary control.

2. Pandemics: Systematic Government Bureaucracy and Coercion versus Spontaneous Social Coordination

2.1. The Theorem of the Impossibility of Socialism and Its Application to the Current Crisis

The reaction of the world’s different governments and public authorities (and particularly those of my own country, Spain) to the emergence and evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic, the interventionist measures they have taken one after the other, and the monitoring of the effects of these measures offer a unique opportunity to any economic theorist who wishes to observe, verify, and apply to a historical case that is very close and significant to us the essential content and main implications of the “theorem of the impossibility of socialism” formulated for the first time by Ludwig von Mises one hundred years ago.10 It is true that the collapse of the former Soviet Union and of real socialism, along with the crisis of the welfare state, had already sufficiently illustrated the triumph of the Austrian analysis in the historic debate about the impossibility of socialism. However, the tragic outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has given us one more real-life example – in this case one much closer to us and more concrete – which superbly illustrates and confirms what the theory holds, namely: that is it theoretically impossible for a central planner to give a coordinating quality to their commands, regardless of how necessary these commands seem, how noble their goal is, or the good faith and effort devoted to successfully achieving it.11

The worldwide impact of the current pandemic, which has affected all countries regardless of tradition, culture, wealth, or political system, highlights the general applicability of the theorem Mises discovered (which we could aptly call the “theorem of the impossibility of statism”) to any coercive, interventionary measure the state uses. It is true that the interventionist measures adopted by the various governments differ considerably. However, though some governments may have managed the crisis better than others, the differences have actually been more of degree than of kind, since governments cannot dissociate themselves from the essential coercion in their very DNA. In fact, coercion is their most fundamental characteristic, and whenever they exercise it, and precisely to the extent they exercise it, all of the negative effects predicted by the theory inevitably appear. Therefore, it is not just that some authorities are more inept than others (though that is certainly the case in Spain12). Instead, it is that all authorities are doomed to fail when they insist on coordinating society through the use of power and coercive commands. And this is perhaps the most important message economic theory must convey to the population: Problems invariably arise from the exercise of coercive state power, regardless of how well the politician of the moment performs.

Although this article deals in general with the economic analysis of pandemics, we will focus almost exclusively on the implications of the current pandemic in light of the “theorem of the impossibility of statism-socialism.” The reason for this is twofold: First, from the viewpoint of any contemporary reader, the current pandemic is closer in time and has a personal impact. Second, the intervention models employed in other pandemics are now quite remote from us in history, and though we can identify many of the same phenomena we have recently observed (such as the manipulation of information by the Allied Powers during the flu pandemic of 1918, poorly named the “Spanish” flu for precisely that reason), they clearly offer less added value today as an illustration of the theoretical analysis.

As I explain in detail in my book Socialism, Economic Calculation, and Entrepreneurship, particularly in chapter 3, which applies directly here,13 economic science has shown that it is theoretically impossible for the state to function in a dynamically efficient way, since it is perpetually immersed in an ineradicable ignorance that prevents it from infusing a coordinating quality into its commands. This is chiefly due to the four factors listed below from least to most important:

First, to truly coordinate with its commands, the state would need a huge volume of information and knowledge – not principally technical or scientific knowledge, though it would need that too, but knowledge of countless specific and personal circumstances of time and place (“practical” knowledge). Second, this vital information or knowledge is essentially subjective, tacit, practical, and inarticulate, and thus it cannot be transmitted to the state central-planning and decision-making agency. Third, this knowledge or information is not given or static, but instead is continually changing as a result of the innate creative capacity of human beings and the constant fluctuation in the circumstances surrounding them. The impact of this on the authorities is dual: They are always late, because once they have digested the scarce and biased information they receive, it has already become outdated; and they cannot hit the mark with their commands for the future, since the future depends on practical information that has not yet emerged because it has not yet been created. And finally, fourth, let us recall that the state is coercion (that is its most fundamental characteristic), and therefore, when it imposes its commands by force in any area of society, it hinders and even blocks the creation and emergence of precisely the knowledge or information the state desperately needs in order to give a coordinating quality to its commands. Thus the great paradox of statist interventionism, since it invariably tends to produce results opposite those it is intended to achieve.14 Typically, and on an extensive scale, we see the emergence, left and right, of maladjustments and discoordination; systematically irresponsible actions on the part of the authorities (who do not even realize how blind they are regarding the information they do not possess and the true cost of their decisions); constant scarcity, shortages, and poor quality in the resources the authorities attempt to mobilize and control; the manipulation of information to bolster themselves politically; and the corruption of the essential principles of the rule of law. Since the outbreak of the pandemic and the mobilization of the state to fight it, we have observed all of these phenomena, which have inevitably emerged, one after the other, in a chainlike fashion. And I repeat, these phenomena do not arise from malpractice by public authorities but instead are intrinsic to a system based on the systematic use of coercion to plan and to try to solve social problems.

As an example, I recommend readers study, in light of the theoretical analysis we are discussing concerning the impossibility of statism, the research article “El libro blanco de la pandemia”15 [White Paper on the Pandemic] written by José Manuel Romero and Oriol Güell. This paper illustrates, step by step, practically all of the inadequacies and deficiencies of statism, even if the authors, who are journalists by trade, naively believe that their description of the events will serve to prevent the same errors from being committed in the future. They fail to grasp that the errors in question are not rooted chiefly in political or management errors, but in the very rationale behind the state system of regulation, planning, and coercion, which always, in one way or another, triggers the same effects of discoordination, inefficiency, and injustice. As one example among many others, we could cite the chronology of events, which the authors have reconstructed perfectly, and the precious weeks that were lost when, beginning February 13, 2020, doctors from the public hospital Arnau de Vilanova in Valencia fought unsuccessfully to obtain authorization from the regional (and national) health authorities to run coronavirus tests on samples they had taken from a sixty-nine-year-old patient who had died with symptoms they suspected might have been caused by Covid-19. But they were confronted with a harsh reality: The corresponding central health planning agencies (the Department of Health in Madrid and the regional health ministry) repeatedly denied authorization for the tests, since the patient suspected of having been infected (who, many weeks later, was shown to have died from Covid-19) did not meet the conditions the authorities had set down earlier (on January 24), namely: having traveled to Wuhan in the fourteen days prior to the onset of symptoms or having been in contact with people diagnosed with the disease. Clearly, in a decentralized system of free enterprise in which the creativity and initiative of the actors involved had not been restricted, this monumental error would not have occurred, and we would have gained several key weeks’ worth of knowledge. We would have known the virus was already freely circulating in Spain and could have learned about preventive measures and ways of fighting the pandemic. (For instance, it would have been possible to cancel, among others, the feminist demonstrations on March 8.)

Also quite noteworthy is Mikel Buesa’s remarkable book (which we have already cited16) in terms of presenting (especially on pages 118 and following) the litany of errors, discoordination, corruption, manipulation of information, violations of rights, and lies that have naturally and inevitably arisen from the activity, at different levels, of the state as it has attempted to come to grips with the pandemic. For instance, “…Spanish manufacturers understandably interpreted the orders of seizure of medical supplies as an attack on their business interests, and the result was a halt in production and imports” (p. 109) just when it was most urgent to safeguard the health of doctors and health personnel, who were going to work every day without the necessary protective measures. Also, seizures in customs by order of the state led to the loss of orders of millions of face masks when the corresponding suppliers preferred to send them to other customers in fear that the government might confiscate the merchandise (ibid.). There was also the case – one among many – of the Galician manufacturer whose materials were frozen in a warehouse by order of the state, but no one claimed them (pp. 110-111). In addition, there were the Spanish companies specialized in the manufacture of PCR tests whose stock and production were requisitioned by the state, and consequently, these companies were not able to produce more than 60,000 PCR tests each day or satisfy domestic and foreign demand (p. 119). And this was compounded by the bottleneck stemming from the lack of cotton swabs for collecting samples, a problem which could have been solved immediately if Spanish producers had been permitted to operate freely (p. 114). There was the widespread shortage which dominated the market for face masks, hand gels, and nitrile gloves as a result of state regulation and the setting of maximum prices, and all during the months of the most rapid spread of the virus (p. 116).17 And of the 971 million units of different products (masks, gloves, gowns, breathing devices, diagnostic equipment, etc.) acquired since the month of March, only 226 million had actually been distributed by September of 2020, while the rest languished in storage in numerous warehouses (p. 118). And the list goes on and on, in an endless catalogue that rather resembles a description of the systematic inefficiencies which existed in production and distribution in the former Soviet Union during the twentieth century and led to the definitive collapse of the communist regime beginning in 1989.18 And I repeat, this has all been due not to a lack of work, management, or even good faith on the part of our authorities, but to their lack of the most fundamental knowledge of economics (and this despite there being philosophy professors and even PhDs in economics at the head of our government.) Therefore, it should not surprise us that, at a moment of utmost urgency and gravity, they chose – as authorities always do, since that is precisely their role in the state’s framework – coercion, regulation, confiscation, etc. instead of freedom of enterprise, production, and distribution and to support instead of hinder private initiative and the free exercise of entrepreneurship.

2.2. Other Collateral Effects of Statism Predicted by the Theory

Apart from the basic consequences of maladjustments, discoordination, irresponsible actions, and a lack of economic calculation, statism brings about all sorts of additional negative effects which are also covered in chapter 3 of my book Socialism, Economic Calculation, and Entrepreneurship.19 Another typical characteristic of statism and the authorities who embody it is the attempt to take advantage of crises – in this case the one the pandemic has caused – to not only hold onto power but (and especially) to increase their power even more by engaging in political propaganda to manipulate and even systematically deceive the citizenry to that end.20 For instance, when the pandemic struck, the Chinese authorities initially tried to conceal the problem by hunting down and harassing the doctors who had sounded the alarm. Later, the authorities launched a shameless campaign of cover-up, lack of transparency, and underreporting of deaths which has lasted until at least the present, since as of this writing (January 2021), over a year after the pandemic broke out, the Chinese government has yet to allow the international commission organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to enter the country and conduct an independent investigation into the true origin of the pandemic.

Regarding the Spanish state, the cited works document multiple lies that have been deliberately and systematically spread in the form of political propaganda to manipulate and deceive citizens so they would be unable to assess the true cost of the government’s management. Of these lies, I would like to highlight the following, due to their significance: First, the true number of deaths. (According to Mikel Buesa, only 56.4 percent have been reported of a total, to date, close to 90,000 – p. 76.) Second, the total number of people really infected (which, depending on the stage of the pandemic, varies between five and ten times the number of cases reported). And third, the false data, inflated by 50 percent, which the government deliberately provided the Financial Times at the end of March 2020 concerning the number of PCR tests administered (355,000 instead of the actual 235,000), numbers the government itself later publicly used to boast that Spain was one of the countries with the most tests performed (see, for instance, p. 113 of Buesa’s book).

We must bear in mind that states in general and their governments in particular invariably focus on achieving their objectives in an extensive and voluntaristic21 manner. “Voluntaristic” since they expect to accomplish their proposed ends by mere coercive will in the form of commands and regulations. “Extensive” since the achievement of the goals pursued is judged only in terms of the most easily measurable parameters – in this case, the number of deaths, which, curiously, has been underreported by nearly half in the official statistics, as we have seen. And as for the prostitution of law and justice, another typical collateral effect of socialism,22 Buesa documents in detail the abuse of power and the wrongful and unconstitutional use of the state of alarm, when the appropriate action would have been to declare a true state of emergency, with all of the protections against government control established by the constitution. Thus, both the “rule of law” and the fundamental content of the constitution were disregarded (Buesa, pp. 96-108 and 122).

Worthy of special mention are the whole chorus of scientists, “experts,” and intellectuals who are dependent on and complicit with the state. They depend on the political establishment and devote themselves to providing supposed scientific support for every decision emanating from it. In this way, they use the halo of science to disarm civil society and render it helpless. In fact, “social engineering” or scientistic socialism is one of the most typical and perverse manifestations of statism, since, on the one hand, it aims to justify the notion that the experts, due to their supposedly higher level of training and knowledge, are entitled to direct our lives; and on the other hand, it aims to block any complaint or opposition by simply mentioning the purported backing of science. In short, governments lead us to believe that, by virtue of the allegedly greater knowledge and intellectual superiority of their scientific advisors with respect to ordinary citizens, governments are entitled to mold society to their liking via coercive commands. Elsewhere23 I have written about the litany of errors triggered by this “power binge,” which is fueled by the fatal conceit of “experts” and technicians. In turn, the origin of this fatal conceit lies in the fundamental error of believing that the dispersed, practical information the actors in the social process are constantly creating and transmitting can come to be known, articulated, stored, and analyzed in a centralized way through scientific means, and this is impossible in both theory and practice.24

2.3. Pandemics: Free Society and Market Economy

We cannot know a priori how a free society not in the grip of the systematic coercion of state interventionism would cope with a pandemic as severe as the current one. As now, society would certainly feel a profound impact in the areas of health and the economy. However, the reaction of society would clearly rest on entrepreneurial creativity. The search for solutions and the efforts made to detect and overcome problems as they arose would be dynamically efficient. It is precisely this force of entrepreneurial creativity which prevents us from knowing the details of the solutions that would be adopted, since entrepreneurial information which has not yet been created – because monopolistic state coercion has prevented its creation – cannot be known today, though, at the same time, we can rest assured that problems would tend to be detected and resolved very agilely and efficiently.25 In other words, as we have been analyzing, problems would be handled in a manner exactly opposite to what we see with the state and the combined action of its politicians and bureaucrats, regardless of the good faith and work they put into their efforts. And although we cannot even imagine the immense variety, richness, and ingenuity that would be rallied to combat problems resulting from a pandemic in a free society, we have numerous indications to give us at least an approximate idea of the completely different scenario that would emerge in an environment free from state coercion.26

For instance, instead of total and all-inclusive confinement – and the obligatory economic standstill associated with it – (which, we must not forget, originated in communist China, no less), in a free society, the measures that would predominate would be far more decentralized, disaggregated, and “micro” in nature, such as the selective confinement of (private) residential areas, neighborhoods, buildings, companies, nursing homes, etc. Instead of the censorship exercised during the key weeks at the start of the pandemic (and the harassment of those who revealed it), information would be transmitted freely and efficiently at great speed. Instead of slowness and clumsiness in the monitoring, via tests, of possible cases, from the very beginning entrepreneurs and proprietors of hospitals, nursing homes, airports, stations, means of transportation, etc. would, in their own interest and in that of their customers, introduce these tests immediately and with great agility. In a free society and a free market, acute shortages and bottlenecks would not occur, except on very isolated occasions. The use of face masks would not be advised against (when half the world has already been using them with good results), nor would it later be frantically imposed in every situation. Entrepreneurial ingenuity would focus on testing, discovering, and innovating solutions in a polycentric and competitive manner, and not, as is the case now, on blocking and deadening most of humanity’s creative potential through monopolistic central state planning.27 And I need not mention the enormous advantage of individual initiative and private enterprise nor how differently they operate in terms of researching and discovering remedies and vaccines; for even in the current circumstances, states have been obliged to turn to them to obtain these things quickly when confronted with the resounding failure of their pompous and well-funded public research institutes to offer effective, timely solutions.28 The same could be said concerning the far greater agility and efficiency of private health care networks (health insurance companies, private hospitals, religious institutions, foundations of all sorts, etc.), which have the additional possibility of expanding much more quickly and with much more elasticity in times of crisis. (As an example, let us recall that in Spain, curiously, nearly 80 percent of public servants themselves – including the vice president of the socialist government – freely choose private over public health care, while their fellow citizens are unjustly denied that choice; and even so, at least 25 percent of them make the sacrifice of paying the additional cost of a private health care policy.) And so on…29

2.4. The Servility and Obedience of Citizens

To conclude this section, perhaps it would be a good idea to ask why, despite all of the inadequacies, insufficiencies, and contradictions inherent in state management that have been exposed by economic analysis,30 most citizens, enticed by their politicians and public authorities, continue to obey them with both discipline and resignation. When his Discourse of Voluntary Servitude appeared back in 1574, Etienne de la Boétie31 identified four factors to explain the servility of citizens toward rulers and authorities, and these factors are still fully relevant even today: the custom of obeying, which, though of tribal and family origin, is extrapolated to the whole society; the perennial self-presentation of political authorities with a “holy” seal (in the past, divine election; today, popular sovereignty and democratic support) which would legitimize the supposed obligation to obey; the perpetual creation of a large group of stalwarts (in the past, members of the Praetorian Guard; today, experts, civil servants, etc.) who depend on the political establishment for their subsistence and constantly support, sustain, and rally behind it; in short, the purchase of popular support through the continual granting of subsidies (in the past, stipends and awards; today, for instance, benefits of the guilefully named “welfare state”), which make citizens progressively and irreversibly dependent on the political establishment. If to this we add the fear (incited by the state itself) which leads people to call on the authorities to do something, especially in times of severe crisis (wars, pandemics), we can understand how citizens’ obsequious behavior grew and was reinforced, particularly in this sort of situation. But as soon as we begin any in-depth study from a theoretical or philosophical standpoint, it becomes clear that the special authority attributed to the state lacks moral and ethical legitimacy. Many have shown this to be true, including Michael Huemer in his book The Problem of Political Authority.32 Obviously, we cannot here delve deeply into this grave problem, which undoubtedly lies at the root of the main social crisis of our time (and, in a certain sense, of all time). However, in the context of our economic analysis of pandemics, what we can confirm is that there exists a “virus” even deadlier than the one that triggered the current pandemic, and it is none other than the statism “which infects the human soul and has spread to all of us.”33

3. The Pandemic as a Pretext for an Increasing Lack of Fiscal and Monetary Control by Governments and Central Banks

3.1. Dynamic Efficiency as a Necessary and Sufficient Condition for the Economy to Recover from a Pandemic

Any economy affected by a pandemic requires a series of conditions which, at first, permit the economy to adapt to the new circumstances at the lowest cost possible and, once the pandemic has been overcome, permit a healthy and sustainable recovery to begin. In the first part of this paper, we considered the possible structural effects that could result from a pandemic in the short, medium, and, eventually, long term and the role the natural increase in uncertainty (caused by the pandemic) initially plays in the increase in the demand for money and in its purchasing power: In the context of (sectoral or general) confinement in which productive activity is temporarily halted, it is particularly important that there be an accompanying decrease in demand, to free up consumer goods and services so that all of the people who are forced to suspend their productive or work activity can continue consuming the minimal amount they need. In other words, the rise in cash balances and the fall in nominal prices make it easier for consumers and economic agents to adapt to difficult circumstances, and at the same time, they enable them all to respond quickly once they can see the light at the end of the tunnel and confidence begins to return. In any case, the economy must be “dynamically efficient”34 if it is to uncover the opportunities that begin to emerge and make it possible for them to be seized and for the recovery to get off the ground. The conditions for dynamic efficiency are provided by everything that permits and facilitates the free exercise of (both creative and coordinating) entrepreneurship by all economic agents such that they are able to channel available economic resources into new, profitable, and sustainable investment projects focused on the production of goods and services which satisfy the needs of citizens and are independently demanded by them in the short, medium, and long term. In an environment like our present one, of strongly controlled economies, the process by which prices characteristic of the free-enterprise system are formed and set must run smoothly and with agility. For this to occur, we must liberalize markets as much as possible, particularly the market for labor and other productive factors, by eliminating all of the regulations which make the economy rigid. In addition, it is essential that the public sector not squander the resources companies and economic agents need first, to cope with the ravages of the pandemic and survive and, later, when things improve, to make use of all their savings and idle resources available to bring about the recovery. Therefore, it is imperative that we proceed with a general reduction in taxes which leaves as many resources as possible in the pockets of citizens and, above all, lowers as far as possible any tax on entrepreneurial profits and capital accumulation. We must remember that profits are the fundamental signal that guides entrepreneurs in their indispensable, creative, and coordinating work. Profits direct them in detecting, undertaking, and completing profitable, sustainable investment projects that generate steady employment. And it is necessary to promote, rather than fiscally punish, the accumulation of capital if we wish to benefit the working classes and, particularly, the most vulnerable. This is because the wages they earn are ultimately determined by their productivity, which will be higher, the higher the per capita volume of capital in the form of equipment goods entrepreneurs make available to them in ever-increasing quantity and sophistication. Regarding the labor market, we must avoid any sort of regulation which decreases the supply, mobility, and full availability of labor to quickly and smoothly return to work on new investment projects. Hence, the following are especially harmful: the setting of minimum wages; the rigidification and unionization of labor relations within companies; the obstruction and, particularly, legal prohibition of dismissal; and the creation of subsidies and grants (in the form of temporary labor force adjustment plans, unemployment benefits, and guaranteed minimum income programs). The combination of these can discourage people from looking for work and from wanting to find a job if it becomes obvious that for many, the more advantageous choice is to live on subsidies, participate in the underground economy, and avoid working officially.35 All of these measures and structural reforms must be accompanied by the necessary reform of the welfare state. We must give the responsibility for pensions, health care, and education back to civil society by permitting those who so desire to outsource their benefits to the private sector via the corresponding tax deduction. (As we pointed out in the last section, each year, nearly 80 percent of the millions of Spanish civil servants freely choose private over public health care. There must be a reason for that…)

Therefore, the most appropriate economic-policy approach or road map for dealing with a pandemic and, especially, recovering from one is quite clear. Some of its essential principles are widely known, and others are an “open secret,” especially to all of those who fall into the trap of fueling populist demagogy by creating false and unattainable expectations among a population as frightened and disoriented as one would expect during a pandemic.36

3.2. Depletion of the Extremely Lax Monetary Policy in the Years Prior to the Pandemic

Let us now focus on the current Covid-19 pandemic, which we have been analyzing and using as our main example in this paper. We could highlight a very significant peculiarity which conditions and impacts the future economic evolution of the pandemic more negatively than would be necessary. In fact, this pandemic emerged and spread throughout the world beginning in 2020 in a context in which central banks worldwide had already initiated an extremely lax monetary policy of zero or even negative interest rates and monetary injections the likes of which, due to their degree of intensity, their widespread nature, and the international coordination involved, had never been seen before in the economic history of mankind. This ultra-lax policy had been adopted many months or even years before the pandemic hit, and central banks had employed it under the guise, first, of aiding the emerging recovery following the Great Recession of 2008 and, later, of dealing with the supposed or real uncertainties which invariably arise from time to time (the populist protectionism of Trump, Brexit, etc.).

In my article on “The Japanization of the European Union,”37 I explain that extremely lax monetary policies implemented by central banks before the emergence of the pandemic have had a counterproductive effect. On the one hand, they have obviously failed to boost prices by close to 2 percent. Indeed, the massive injection of money has largely been neutralized, in an environment of great institutional rigidity and uncertainty, by an accompanying widespread increase in the demand for money by economic agents, since the opportunity cost of holding cash balances has been reduced to zero. Furthermore, clear opportunities for sustainable investment are not opening up in an environment of constant regulation and economic interventionism that weighs down expectations of profit and prevents a full recovery of the confidence lost beginning in the Great Recession of 2008. As a result, it has also not been possible to complete the necessary rectification of all the investment errors committed during the bubble and credit expansion years prior to 2008. On the other hand, the moment central banks launched their policies of massive monetary injections, quantitative easing, and zero interest rates, they eliminated ipso facto any incentive the different governments (of Spain, Italy, France, etc.) might have had to introduce or carry through the pending economic, regulatory, and institutional reforms essential to fostering an environment of confidence in which entrepreneurs are free of unnecessary restrictions and obstacles and can devote themselves to putting their creativity into practice and making long-term investments that provide sustainable jobs. Indeed, what government is going to bear the high political cost of, say, putting its accounts on a sound footing and liberalizing the labor market if, de facto, regardless of the deficit incurred, the central bank will finance it directly or indirectly and at zero cost – that is, by completely monetizing it? For instance, the European Central Bank already owns nearly one third of the sovereign debt issued by Eurozone member states, and the moment it launched its policy of indiscriminate purchasing of this debt, it halted the entire process of economic and institutional reform the member states desperately needed. The conclusion that emerges from economic theory could not be plainer: In a context of great institutional rigidity and economic interventionism, ultra-lax monetary policies serve only to indefinitely maintain the rigidity and lethargy of the economies affected and to increase the indebtedness of the respective public sectors to an extent very difficult to sustain.

3.3. The Reaction of Central Banks to the Unexpected Outbreak of the Pandemic

It was in these very worrisome economic circumstances, in which central bankers had already practically depleted their entire arsenal of unconventional, ultra-lax monetary-policy tools, that the Covid-19 pandemic unexpectedly broke out in January of 2020. The reaction of monetary authorities has been simply more of the same: They have redoubled monetary injections even further. To do so, they have expanded their financial-asset purchase programs (and the price, much to the delight of large investors, such as mutual funds, hedge funds, etc., has continuously risen, and in this way, central banks have made the fortunes of a few people even greater, while the economy of most citizens is contracting and entering a recession). In addition, the new money is, de facto, increasingly being distributed through direct grants and subsidies financed via monetized public deficit, such that a large portion of the newly created money is already starting to reach the pockets of households directly. However, since at least as far back as 1752, when Hume38 pointed it out, we have known that the mere equal distribution of monetary units among the citizenry has no real effect.39 For this reason, monetary authorities ultimately do not wish to even hear about Friedman’s famous “helicopter money” as a tool of their monetary policy, since the latter produces apparent expansionary effects only when just a few sectors, companies, and economic agents initially receive the new money, which is accompanied by all of the collateral effects of an increase in inequality in the distribution of income in favor of a small group. (I mentioned this group in connection with the effects of quantitative-easing policies as a determining factor in the enrichment of actors in financial markets.) In any case, it is certain that, sooner or later, and to the extent that it is not sterilized by private banks40 and unmotivated entrepreneurial sectors, the new money will end up reaching the pockets of consumers and generating inflationary pressures, as the Hume effect of an inexorable loss in the purchasing power of the monetary unit appears. And this effect will become increasingly obvious as the initial uncertainty of households is gradually overcome and their members no longer feel the need to maintain such high cash balances or they are simply obliged to spend the money they receive in the form of subsidies to subsist while they are unemployed and unable to produce. At any rate, everything points in the same direction: A growing monetary demand on a production which has declined due to the pandemic leads inevitably to an increasing upward pressure on prices.41 And that is precisely what has already begun to appear as I write these lines (January 2021). For instance, the price of agricultural products has continued to rise and has reached its highest point in three years. Freight charges and the prices of many other raw materials (minerals, oil, natural gas, etc.) have also soared, even to record highs…

3.4. Central Banks Have Gone Down a Blind Alley

The conclusion could not be more obvious. Central banks have truly gone down a blind alley. If they make a forward escape and even further advance their policy of monetary expansion and monetization of an ever-increasing public deficit, they run the risk of provoking a grave crisis of public debt and inflation. But if, in fear of moving from a scenario of “Japanization” prior to the pandemic to one of near “Venezuelization” after it, they halt their ultra-lax monetary policy, then the overvaluation of public-debt markets will immediately become clear, and a serious financial crisis and economic recession will follow and will be as painful as it is healthy in the medium and long term. In fact, as the “theorem of the impossibility of socialism” shows, central banks (true financial central-planning agencies) cannot possibly correctly determine the most suitable monetary policy at all times.

It is very enlightening, in the extremely difficult situation we now obviously find ourselves in, to pay attention to the reactions and recommendations which are ever more anxiously and restlessly (I would even say “hysterically”) coming from investors, “experts,” pundits, and even the most renowned economic and monetary authorities.

For instance, new articles and commentaries appearing continually (particularly in salmon-colored newspapers, starting with the Financial Times) invariably tend to reassure markets and send the message that zero (and even negative) interest rates are here to stay for many years to come, because central banks will not deviate from their ultra-lax monetary policies, and thus, investors can relax and continue to get rich by trading in the bond markets. Central bankers, in turn, overcautiously announce a revision of their inflation targets to make them more flexible (obviously in an upward direction) on the pretext of compensating for the years they have been unable to achieve them and to justify not taking monetary-control measures even if inflation skyrockets.42 Other advisors of the monetary authorities even propose abandoning the inflation target and directly setting the target of adherence to a certain curve of – especially low – interest rates (that is, zero or even negative rates for many years of the rate curve, for which all open-market operations necessary would be carried out). And all of this is applauded by representatives of so-called “Modern Monetary Theory,” which, despite its name, is neither modern nor monetary theory, but simply a potpourri of old Keynesian and mercantilist recipes more characteristic of the utopian dreamers of centuries past (since they hold that the deficit is irrelevant because it can be financed without limit by issuing debt and monetizing it) than of true economic theorists; this theory is wreaking havoc among our economic and monetary authorities.43 Now we come to the last of the “bright ideas,” one that is becoming increasingly popular: the cancellation of the public debt purchased by central banks (which, as we have seen, already amounts to nearly one third of the total).

First of all, the growing number joining the chorus in favor of this cancellation clearly give themselves away, for if, as they affirm, central banks will always repurchase at a zero interest rate the debt issued to meet maturities as they come due, no cancellation will be necessary. The mere fact that people are requesting it precisely now reveals their anxiety at the increasing signs of a rise in inflation and their accompanying fear that fixed-income markets will collapse and interest rates will go back up. Under such circumstances, they consider it crucial that the pressure on wasteful governments be reduced by a cancellation which would amount to a remission of nearly one third of the total debt issued by those governments. Such a cancellation, it is felt, would be detrimental only to an institution as abstract and removed from most of the public as is the central bank. But things are not as straightforward as they seem. If a cancellation like the one now being requested were carried out, the following would become obvious: First, central bankers have limited themselves to creating money and injecting it into the system through financial markets, thus making a few people exorbitantly rich without achieving any significant, real, long-term effects (besides the artificial reduction in interest rates and the simultaneous destruction of the efficient allocation of productive resources).44 Second, the popular outcry against this policy would be so great were this cancellation to occur that central banks would lose not only all credibility,45 but also the possibility of pursuing in the future their open-market-purchase policies (quantitative easing). Under these circumstances, central bankers would be obliged to confine themselves to giving money injections directly to citizens (Friedman’s “helicopter money”). These would be the only “equitable” injections from the standpoint of their effects on income distribution, but since they would lack any real expansionary effects observable in the short term, they would mean the definitive end of central banks’ capacity to influence economies noticeably in the future via monetary policy.

In this context, the only sensible recommendation that can be given to investors is that they sell all their fixed-income positions as soon as possible, since we do not know how much longer central banks will go on artificially keeping the prices of these securities more exorbitant than they have ever been in history. In fact, there is more than sufficient evidence that the most alert investors, like hedge funds and others, by the use of derivatives and other sophisticated techniques, are already betting on the collapse of fixed-income markets, while, officially, they continue to leak reassuring messages and recommendations to the press through the most prestigious commentators.46 This should come as no surprise, since they wish to get out of the debt markets without being noticed and at the highest price possible.

3.5. The “Pièce de Résistance” of Public Spending

And now we come to the last recipe offered as essential for overcoming the crisis caused by the pandemic and returning to normalcy: Forget about putting the public accounts on a sound footing or trimming unproductive public spending from them. Forget about reducing tax pressure or lightening the burden of bureaucracy and regulation for entrepreneurs so they recover confidence and embark on new investments. Forget about all of that; the exact opposite is called for: We must rely on fiscal policy as much as possible and increase public spending even further – disproportionately – although, we are told, priority should be given to investments in the environment, digitalization, and infrastructure. But this new death throe of fiscal policy is procyclical and disturbingly counterproductive. For instance, by this summer (2021), when the “manna” of 140 billion euros provided to Spain by the European Union on a non-reimbursable basis begins to arrive (of a total program of 750 billion organized by EU authorities and expandable to 1.85 trillion in loans), it is more than probable that the economies of both Spain and the other EU countries will already be recovering on their own. Hence, these funds will absorb and divert scarce resources essential to the ability of the private sector to initiate and complete the necessary investment projects which, because they are truly profitable, can, by themselves and without public aid, generate a high volume of sustainable employment in the short, medium, and long term. Such jobs differ strikingly from the invariably precarious work which depends on political decisions that lead to consumptive public spending, even if on grandiose environmental and digital “transition” projects. And we need not even mention the inherent inefficiency of the public sector when it comes to directing resources received and the inevitable politicization of their distribution, which is always highly vulnerable to those seeking the benefits and maintenance of the political spoils system. We all remember, for instance, the abysmal failure of “Plan E,” which involved the injection of public spending and was promoted by Zapatero’s socialist administration to cope with the Great Recession of 2008. We also remember the unfortunate failure of Japan’s fiscal policy of large increases in public spending, which has had no other noticeable effect than to make Japan the most indebted country in the world. In short, history repeats itself again and again.

Conclusion

There are no miraculous shortcuts to overcoming a crisis as severe as the one caused by the current pandemic. Even if governments and monetary authorities strive to present themselves to citizens as their indispensable “saviors,” due to their frenetic activities and efforts in doing apparently beneficial things. Even if all of these authorities systematically hide their intrinsic inability (as the Austrian School has shown) to hit the mark and obtain the information they need to infuse a coordinating quality into their commands. And even if their actions are systematically irresponsible and counterproductive, since they squander society’s scarce resources and preclude the correct allocation of resources and rational economic calculation in investment processes. In spite of it all—that is, in spite of governments and central banks, a few years from now the Covid-19 pandemic will merely be a sad historical memory that will soon be forgotten by future generations, just as no one remembered the “Spanish flu” of a century ago and the far greater toll it took on the economy and the health of the population. Now, like then, we will get through thanks to our individual and collective effort in striving to creatively get our life projects off the ground in the small areas which, in spite of everything, remain open for free enterprise and the uncontrolled market.

- 1. I will always remember my friend Arthur Seldon’s story about losing his parents. After graduating from the London School of Economics, Seldon went on to become, together with Lord Harris of High Cross, a Founder President of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in London, a distinguished member of the Mont Pelerin Society, a great writer on a wide range of subjects, and a defender of the market economy. Both of Seldon’s parents passed away from the Spanish flu within a short time of each other – at the age of thirty – when he was just two years old. So, when Arthur Seldon was still a very young child, he became an orphan and was later adopted. With time, he managed to overcome the traumatic experience, but it left him with a permanent stutter that stayed with him for the rest of his life. It did not stop him from becoming one of the UK’s most brilliant economists and, to a large extent, the inspirer of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative revolution, which began in the late 1970s. See Arthur Seldon, Capitalism (Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 1991).

- 2. See, for example, Murray N. Rothbard, America’s Great Depression, 5th ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000).

- 3. See, for instance, Carlo Maria Cipolla’s comments on the effects of the fourteenth-century Black Death in his book The Monetary Policy of Fourteenth-Century Florence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982) and my critique of his remarks in Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles, 4th ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2020), pp. 71-72 and especially note 56. However, the destructionist paranoia reaches its peak in Paul Krugman, who in his 2011 article “Oh! What A Lovely War!” actually states, “World War II is the great natural experiment in the effects of large increases in government spending, and as such has always served as an important positive example (!) for those of us who favor an activist approach to a depressed economy.” Cited by J.R. Rallo in his foreword to Murray N. Rothbard’s book La gran depresión (Madrid, Unión Editorial, 2013), pp. XXVI-XXVII. For the original English, see America’s Great Depression, op. cit.

https://business.time.com/2011/08/16/paul-krugman-an-alien-invasion-could-fix-the-economy/

- 4. “…All, as if they looked for death that very day, studied with all their wit, not to help to maturity the future produce of their cattle and their fields and the fruits of their own past toils, but to consume those which were ready to hand.” See G. Boccaccio, the Decameron, Day the First [https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23700/23700-h/23700-h.htm#Day_the_First] and the comments which, based on John Hicks’s related remarks (Capital and Time: A Neo-Austrian Theory, Clarendon, Oxford, 1973, pp. 12-13), I make in Jesús Huerta de Soto, Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles, 4th ed. (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2020), pp. 71-72 and 346.

- 5. Ibid., pp. 344-346.

- 6. Of course, I am not referring here to errors that already existed before the pandemic and are still awaiting liquidation or restructuring.

- 7. In the case of the “Spanish flu,” this period lasted a little over two years. As for the current Covid-19 pandemic, in spite of the vaccines, we believe this second phase will have a similar duration, though it may end a few months sooner.

- 8. See, among many other studies, the one by Hans Rosling, Factfulness (London: Sceptre, 2018).