A brief look at the lives of Rousseau, Marx, Guevara, Brecht, and Sartre suggests that many of the Left’s most celebrated heroes built their philosophies on a foundation of the most repugnant narcissism, violence, and inhumanity.

Introduction

In editing David Hume’s 1766 pamphlet titled About Rousseau, Lorenzo Infantino has drawn attention to a dispute between the two philosophers that at the time caused much discussion throughout Europe. At the core of that contrast were not only two different world views, David Hume’s classical liberal and individualist weltanschauung versus Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s egalitarian and collectivist one, but also two very different personalities: the Scottish thinker was mild mannered, humble, and reserved, while the philosopher from Geneva was megalomaniacal, paranoid, and quarrelsome.1

The relationship between the two represents an interesting historical episode. When Rousseau became wanted by the police in Continental Europe for his subversive writings, Hume, who empathized with the precarious situation in which the Swiss philosopher found himself, generously offered to host him in his house in England. In addition, he also made an effort with the authorities to get him a living and a pension. However, following a hoax organized by Horace Walpole against Rousseau (specifically a fake letter which was published in the newspapers), the latter was convinced, wrongly, that Hume was the head of a “clique” of enemies who had conspired against him. Hence the irreparable break between the two, in which Hume, unwillingly and only on the insistence of his friends, answered to Rousseau’s unpleasant public accusations.

The Moral Credentials of the Committed Intellectual

In the story of the stormy relationship between Hume and Rousseau there appears a figure that has become typical of contemporary times, the socially engaged intellectual, who emerged precisely in this period and of whom Rousseau was probably the original prototype. Indeed, in the eighteenth century, with the decline of the power of the church, a new character emerged, the lay intellectual, whose influence has continually grown over the last two hundred years. From the beginning the lay intellectual proclaimed himself consecrated to the interests of humanity and invested with the mission of redeeming it through his wisdom and teaching.

The progressive intellectual no longer feels bound by everything that belonged to the past, such as customs, traditions, religious beliefs: for him all the wisdom accumulated by humanity over the centuries is to be thrown away. In his boundless presumption, the socially engaged intellectual claims to be able to diagnose all of society’s ills and to be able to cure them with the strength of his intellect alone. In other words, he claims to have devised and to possess the formulas thanks to which it is possible to transform the structures of society, as well as the ways of life of human beings, for the better.

But what moral credentials do committed intellectuals like Rousseau and his many heirs, who claim to dictate standards of behavior for all of humanity, have? In fact, if we look at their lives, we often find a constant: the more they proclaimed their moral superiority, their dedication to the common good, and their selfless love for humanity, the more despicably and unworthily they behaved with the people they dealt with in everyday life, with family members, friends, and colleagues.2

The Distorted Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for instance, opposed all aspects of civilization, starting from the arts and the sciences. As he wrote in his famous 1750 Discours sur les sciences et les artes, which gave him overnight fame: “When there is no effect, there is no cause to seek. But here the effect is certain, the depravity real, and our souls have been corrupted in proportion to the advancement of our Sciences and Arts to perfection.”3

In his second Discourse on Inequality and in his other works, this contempt for the arts and the sciences quickly extended to a contempt for industry, capital accumulation, commerce, private property, and the family.

Institutions that many would regard as responsible for the development of civilization were, according to Rousseau, the source of human corruption and evil. Man was originally good, and he was made bad solely by institutions and the development of civilizing forces. Telling, in this regard, are the words with which he began The Social Contract: “Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains.”4 In the eyes of Thomas Sowell this phrase neatly summarized the heart of the vision of the anointed intellectual. According to Rousseau, writes Sowell, “[t]he ills of society are seen as ultimately an intellectual and moral problem, for which intellectuals are especially equipped to provide answers, by virtue of their greater knowledge and insight as well as their not having vested economic interests to bias them in favor of the existing order and still the voice of conscience.”5

Rousseau’s sentimentalist view of human nature and his prejudice toward institutions, observed Roger Scruton, was typically adolescent, immature, prejudicial, and hysterical, throwing “to the winds the common sense and political sagacity which motivated Hobbes and Locke.”6

Rousseau was the first to repeatedly proclaim himself a friend of all mankind, but while he loved mankind in general, he was prone to quarrel constantly with concrete, flesh-and-blood human beings and to exploit everyone he had to deal with, especially those who made the mistake of treating him well, such as the loveable David Hume, the mild-mannered Denis Diderot, the great physician Théodore Tronchin, the deist François-Marie Arouet (better known as Voltaire), and the numerous women who supported him.7 Tibor Fischer described him as “a man who made a career out of spite.”8

Rousseau’s biographers paint him as a monster of vanity, selfishness, and ingratitude, which is why he has been characterized as one of the least likeable of all political philosophers. As the historian of political thought Gerard Casey writes,

Rousseau is a figure whom many people love to hate. And there’s good reason for this. He was self-centred, vain, self-pitying, narcissistic, and he yoked all these unattractive traits to an irrepressible lust for self-publicity. An Angry Young Man before his time, he made the common mistake of confusing rudeness and boorishness with honesty and integrity, betraying a bumptiousness that probably resulted in knowing that he could never hope to move by right in the highest social circles to which he aspired.9

Rousseau portrayed himself as a man devoted to love, but never showed any real affection toward his parents, his brother, his partner, nor, above all, his children. In fact, Rousseau, even though he stood out as a master of pedagogy, pretending with his treatise Emile to set the basis for a new and better way of approaching education, behaved in the most unnatural and unpleasant way toward his children. With his domestic partner and mistress, Marie-Thérèse Levasseur, he had five children and decided to abandon each of them in an orphanage. What was even worse was his justification for he claimed that at the hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés they would be better provided for in every way. Like all his contemporaries, however, Rousseau knew very well indeed that in those days the living conditions in the orphanages were terrible: only five to ten children out of a hundred survived into adulthood, and almost all of those who survived ended up as beggars or vagrants. The real reason for the abandonment was the philosopher’s lack of care and love toward his five children. Demonstrating this was the fact that Rousseau did not even note their date of birth and never worried about their fates.10

Karl Marx, the Racist Exploiter

Such personalities are surprisingly common among revolutionary intellectuals. Karl Marx’s taste for verbal violence and for overpowering his opponents were also well known, as was his tendency to exploit those around him, a fact which was noticed by many of his contemporaries. One of these was the Italian revolutionary of the Risorgimento Giuseppe Mazzini, who once described the philosopher from Trier as

a destructive spirit whose heart was filled with hatred rather than love of mankind … extraordinarily sly, shifty and taciturn. Marx is very jealous of his authority as leader of the Party; against his political rivals and opponents he is vindictive and implacable; he does not rest until he has beaten them down; his overriding characteristic is boundless ambition and thirst for power. Despite the communist egalitarianism which he preaches he is the absolute ruler of his party … and he tolerates no opposition.11

Marx quarreled furiously with all those with whom he associated, unless he could dominate them. Gustav Techow, a Prussian military officer who got to spend time with Marx when the revolutionary group he was associated with in Switzerland sent him to London, upon returning reported to his associates that “[d]espite all of his assurances to the contrary … personal domination is the end-all of his every activity.”12 Marx despised his opponents, uttering words and comments we would squarely call racist.13 Well known, for instance, are the words Marx employed to discredit a fellow socialist, Fernand Lassalle, in one of his correspondences with Friedrich Engels on July 30, 1862:

The Jewish Nigger Lassalle who, I am glad to say, is leaving at the end of this week … had the insolence to ask me whether I would be willing to hand over one of my daughters to la Hatzfeldt as a “companion”, and whether he himself should secure Gerstenberg’s (!) patronage for me! … Add to this, the incessant chatter in a high, falsetto voice, the unaesthetic, histrionic gestures, the dogmatic tone! … It is now absolutely clear to me that, as both the shape of his head and his hair texture shows—he descends from the Negros who joined Moses’s flight from Egypt…. Now this combination of Germanness and Jewishness with a primarily Negro substance creates a strange product. The fellow’s importunity is also nigger-like.

Marx’s racism explains his infatuation for the theories of the French ethnologist Pierre Trémeaux, who in an obscure book claimed that “[t]he backward negro is not an evolved ape, but a degenerate man.” In light of this “finding,” the author of The Communist Manifesto, considered Trémeaux and his works to be “a very significant advance over Darwin,” as he wrote to Engels in 1866. This racism, moreover, led him to support with enthusiasm the United States’ aggressive war on Mexico, the annexation of Texas and California, the French conquest of Algeria, and the ruthless colonial rule of the British in India.14 These events were all lauded under the banner of “progress.” Marx believed that the “Negro race” stood outside of history, a view he got from reading Hegel’s account of sub-Saharan Africa in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History.15 Like Hegel, moreover, he believed that slavery could not be abolished in one fell swoop without destroying civilization. Not only was the “Negro race” not ready for freedom, but slavery served an indispensable economic function. As he wrote in The Poverty of Philosophy:

Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that gave colonies their value; it is the colonies that created world trade, and it is world trade that is the precondition of large-scale industry. Thus slavery is an economic category of the greatest importance…. Wipe out North America from the map of the world and you will have anarchy—the complete decay of modern commerce and civilization. Abolish slavery and you will have wiped America off the map of nations.16

What Marx shared most notably with Rousseau was a tendency to quarrel with friends and benefactors. He made Friedrich Engels subsidize him, demanded money from everyone, and regularly squandered the money on the stock market or in other ways, condemning family members to a precarious life. What stands out was Marx’s tyrannical treatment of his wife and daughters. In his own works Marx complained about the low wages of the working class, yet he never had the courage nor the humility to visit a factory. He referred to proletarians as “dolts” and “asses.”

The only member of the working class Marx knew was his own indefatigable housekeeper, Helen Demuth, whom he exploited indecently. Throughout all his life he never gave her a penny, just food and accommodation. While living under the same roof with his wife and his legitimate children, Marx was accustomed to use her as a sex object, up to the point of getting her pregnant. In 1851, out of this adulterous relationship, a son, Frederick Demuth, was born, yet Marx never wanted to have anything to do with him. Freddy was forbidden to be around when Marx was at home and his access was restricted to the kitchen. In order to avoid any social embarrassment he refused to recognize the child, asking Engels to privately acknowledge him instead.

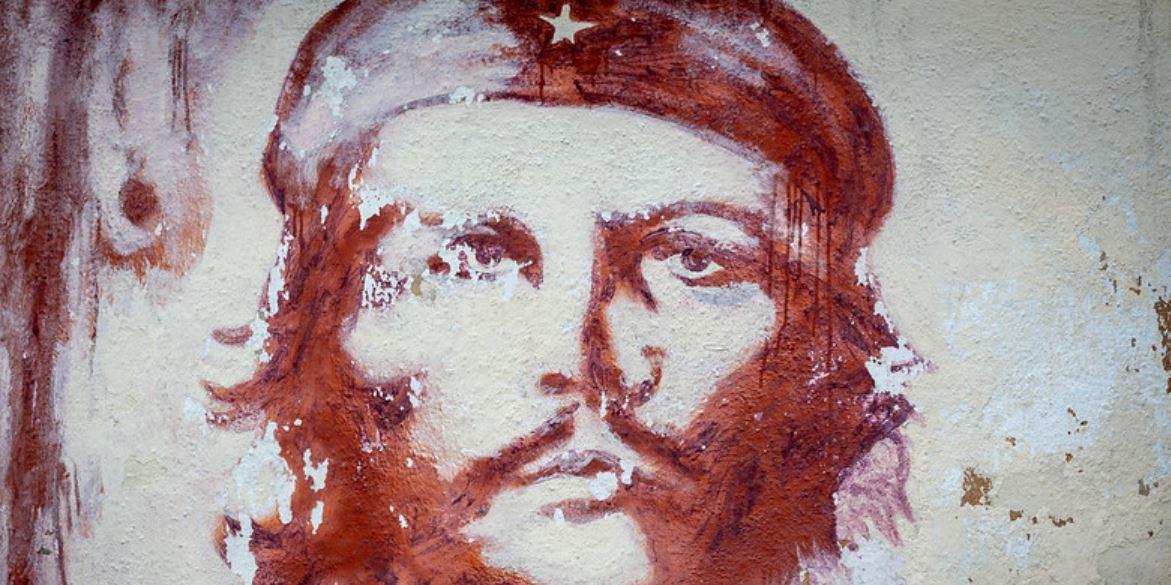

Che Guevara, the Cold-Blooded Killing Machine

In the biographies of so many other leftist icons we find, with surprising regularity, the same moral and personality traits as those present in Rousseau and Marx. Men who are still exalted today, such as Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, were thirsty for power and domination over others, and their fierce language expressed all their contempt for human life.

One of the most extraordinary objects of false propaganda is Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la Serna, the iconic revolutionary behind the Castrist takeover of Cuba. Che Guevara, in fact, has been exalted by the most important maîtres a penser of the Left. Nelson Mandela, for instance, referred to him as an “inspiration for every human being who loves freedom,” while Jean Paul Sartre in 1961 went as far as to write that Che was “not only an intellectual but the most complete human being of our age.”17 Testimonies from people who were close to him, however, tell a different story, for they describe Che Guevara as a “killing machine.” He took great pleasure in cold killing, and personally shot or executed hundreds of people without trial, only on the basis of suspicion. As a perfect Machiavellian, Che believed that everything, even the cruelest of all methods and actions, was justified in the name of the revolution. Equality before the law, judicial proof, habeas corpus, the principle of in dubio pro reo, were all remnants of bourgeois society that would have to be subordinated to the prime objective: the communist revolution and the making of the new socialist man. As he put it: “To send men to the firing squad, judicial proof is unnecessary. These procedures are an archaic bourgeois detail. This is a revolution! A revolutionary must become a cold killing machine motivated by pure hatred.”18 Speaking from experience, in his “Message to the Tricontinental” of April 1967, Che summarized his idea of justice: “[H]atred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine.”19

Che Guevara’s propensity for violence is something that characterized his persona even before the actual takeover of Cuba. During his period of preparation in the Movimiento 26 de Julio, Che’s psychotic personality, along with his hatred and his systematic prejudices, did not go unnoticed among his fellow fighters, who in fact called him “el saca muelas”—the molar puller. It was at a young age that he developed the view that there is an inextricable link between violence and social change. “Revolution without firing a shot? You’re crazy,” he told his friend Alberto Granado during their journey across South America.

This man’s lust for power and love for killing is best illustrated by his period in charge of La Cabaña prison in the aftermath of the revolution. Between January and June of 1959, as head of the Comisión Depuradora, which was responsible for cleansing the country of political opponents and dissenters, Che was directly responsible for the killing of over five hundred men, inaugurating one of the darkest periods of Cuban history. The dynamics of the procedures used at La Cabaña were well captured by a member of the judicial body, José Vilasuso: “The process followed the law of the Sierra: there was a military court and Che’s guidelines to us were that we should act with conviction, meaning that they were all murderers and the revolutionary way to proceed was to be implacable…. Executions took place from Monday to Friday, in the middle of the night…. On the most gruesome night I remember, seven men were executed.”20

For Che Guevara violence was not only permissible but necessary for the triumph of the revolution: “The peaceful way is to be forgotten and violence is inevitable. For the realization of socialist regimes, rivers of blood will have to flow in the name of liberation, even at the cost of millions of atomic victims.” As Leonardo Facco thus concludes: “Hatred, violence, murder, shooting, death, revenge, torture, are the words that best describe Ernesto Che Guevara.”21

Bertolt Brecht, Servile Flatterer of Tyrants

The German playwriter Bertolt Brecht, still much studied in schools today, is a typical example of the left-wing intellectual who puts himself at the service of a ruthless dictatorship in exchange for official honors and privileges. This Faustian deal had a significant imprint on his life and works. In the 1930s Brecht justified all of Joseph Stalin’s crimes, even when the purges concerned his friends. Like Che Guevara, Brecht did not care whether Stalin’s victims were innocent human beings or not. Quite the contrary. When Sidney Hook brought to his attention that innocent former Communists, like Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, were being arrested and imprisoned, he answered: “As for them, the more innocent they are, the more they deserve to be shot.”22

After World War II Brecht served the East German regime, endorsing all its international initiatives and becoming the most trusted of all the writers recruited by the Communist Party. In return for this, he received enormous privileges. He always had large sums of foreign currency at his disposal and traveled constantly abroad, where he and his wife did most of their shopping; even in East Germany he had access to stores that were open only to party officials and other privileged people.

In the meanwhile, however, the masses of whom he claimed to be a champion (but whom he privately despised) were at the mercy of the regime’s rationing policy and almost starving. Around six thousand citizens had in fact taken refuge in West Berlin alone. On June 15, 1953, a workers’ revolt against the socialist regime broke out in East Berlin, and it was soon suppressed with the help of Soviet tanks. Brecht seized the opportunity to earn further recognition and appreciation from the regime by publicly accusing the rioters of being a “fascist and warmongering rabble” composed of “all kinds of déclassé young people.”23 As his private diaries illustrate, however, Brecht knew the truth: these were no fascist agitators at all, but rather common German workers who could not stand a regime that was expropriating their liberties and means of sustenance. The playwright, however, like Marx before him, while dressing like a prole and pretending to be one, was absolutely disinterested in the conditions of the working class—a point that was so evident as to cause fellow socialists, like Theodore W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, to look down upon him. Since he despised German workers, he opposed every attempt of democratization. When a plumber approached him claiming he wanted free elections in order to have the ability to discard corrupt politicians, he answered that under free elections the Nazis would take over, indicating that there was no viable escape route from Soviet colonialism. One had to stick with it.

Like Rousseau and Marx, Bertolt Brecht had, to say the least, a promiscuous and disorderly sexual and family life. He very much liked to run sexual collectives with himself as the master and used to play around with many women in tandem, marrying and divorcing multiple times. This promiscuous sexual life ultimately led him to have two illegitimate children. Like his intellectual predecessors, however, he never showed any interest in his children, whether legitimate or illegitimate. He saw them very rarely, and when he did, he could not stand the time he passed with them, for in his view they destroyed his peace of mind. In this sense he perfectly expressed that kind of intellectual idealism which has distinguished the “anointed intellectual” since the times of Rousseau, caring not one iota about the people around him. One of his former collaborators, W.H Auden, described Brecht as “a most unpleasant man, an odious person,” going as far as to state that in light of his immoral behavior he deserved the death penalty.

Paul Johnson summarized very well the main tenets of Brecht’s corrupt personality: “Ideas came before people, Mankind with a capital ‘M’ before men and women, wives, sons or daughters. Oscar Homola’s wife Florence, who knew Brecht well in America, summed it up tactfully: ‘in his human relationships he was a fighter for people’s rights without being overly concerned with the happiness of persons close to him. Brecht himself argued, quoting Lenin, that one had to be ruthless with individuals to serve the collective.”24

Jean-Paul Sartre, the Spiritual Father of Pol Pot

One of the most hailed maîtres à penser of the Left, but whose influence was disastrous for humankind, was Jean-Paul Sartre. During World War II, when France was occupied by the National Socialists, Sartre behaved with extreme opportunism. He was called to teach philosophy at the famous lycée Condorcet, whose teachers were mostly in exile, hidden, or in concentration camps. He did nothing for the resistance. For the deported Jews he did not move a finger and did not write a word. Rather, he concentrated exclusively on his own career.

After the war ended, Sartre took advantage of the situation and became a celebrity by espousing the causes of the radical Left while preaching his smoky existentialist philosophy. At its core, existentialism was a philosophy of action, a belief that it is a man’s actions not his words, deeds, or ideas, that determine his character and significance. The French socialist, however, came short of applying this principle in his life. Throughout his entire career, as Albert Camus once wrote, Sartre “tried to make history from his armchair.”25

Sartre was linked to the writer Simone de Beauvoir, who behaved throughout her life as his submissive slave, accepting that Sartre openly cheated on her with the many women in his harem. “In the annals of literature,” observes Paul Johnson, “there are few worse cases of a man exploiting a woman.”26 This was all the more extraordinary since Beauvoir was the progenitor of the so-called second-wave feminism. While in her works, specifically in her most important book, The Second Sex, Beauvoir repeatedly opposed male domination and incited females to escape from their biologically determined status of subordination and become full-fledged women, her life represented the opposite of what she preached.27 Feminism and male domination went hand in hand.

Sartre always maintained an embarrassed silence on the topic of Stalin’s concentration camps. The two-hour interview he gave in July 1954, on his return from a trip to the Soviet Union, is among the most abject descriptions of the Soviet state that a renowned intellectual has given to the Western world since that of George Bernard Shaw in the early 1930s.28 Many years later he declared that he had lied. In the following years he extolled with meaningless words Fidel Castro’s Cuba (“The country that emerged from the Cuban revolution is a direct democracy”), Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslavia (“It is the realization of my philosophy”), and Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt (“Until now I have refused to speak of socialism in connection with the Egyptian regime. Now I know I have been wrong”).29 Particularly warm, moreover, were the words he reserved for Mao’s China.

His preaching had deleterious consequences. Although he was not a man of action, he continually incited others to engage in violence. Because he was widely read among the young, he soon became the theoretical godfather of many terrorist movements in the 1960s and 1970s. By inflaming African revolutionaries, he contributed to the civil wars and mass murders that convulsed that continent after decolonization. But even more baleful was his influence in Southeast Asia. Pol Pot and almost all the other leaders of the Khmer Rouge, who brutally murdered more than a quarter of the Cambodian population from 1975 to 1979, had studied in Paris during the 1950s, and it was there that they had absorbed the Sartrean doctrine of the necessity of violence. Those mass murderers were therefore his ideological children.30

When Sartre died in 1980, a huge crowd composed mainly of young people gathered at his funeral and paid him the same honors Rousseau received in his time. Over fifty thousand people decided to follow his corpse into the Montparnasse Cemetery. “To what cause had they come to do honor?” wondered puzzled Paul Johnson, “What faith, what luminous truth about humanity, were they asserting by their mass presence? We may well ask.”31

The True Masters

It is very difficult to find a bad teacher of thought who was not also a bad teacher of life. John Maynard Keynes, for instance, as Murray N. Rothbard recalled in his intriguing Keynes, the Man, was an arrogant and sadistic individual, a bully intoxicated by power, a deliberate and systematic liar, an irresponsible intellectual, a short-lived hedonist, a nihilist enemy of bourgeois morality who hated savings and wanted to annihilate the creditor class, an imperialist, an anti-Semite and a fascist.32

If, on the other hand, we look at those thinkers who defended individual freedom, we almost always find men of very different temperament. David Hume was the opposite of Rousseau: a mild, quiet, affable, commonsense person who devoted his entire life to academia and high theory. Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, Frédéric Bastiat, and Luigi Einaudi had similar characters.

Emblematic is the story of the great French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, who in 1799 was appointed one of the hundred members of the Tribunate and in 1803 published his main work, the brilliant Treatise on Political Economy. Napoleon Bonaparte offered him forty thousand francs a year if he rewrote some parts of the book in order to justify his interventionist economic projects. Say, however, refused the bribe to betray his convictions and was removed from his position as tribune. As the founder of the French liberal school explained in his first letter to Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours on April 5, 1814: “During my period as tribune, not wanting to deliver orations in favour of the usurper, and not having the permission to speak against him, I drafted and published my Traite de Economie Politique. Bonaparte commanded me to attend him and offered me 40 thousand francs a year to write in favour of his opinion. I refused, and was caught up in the purge of 1804.”33

In order to earn a living, Say decided to engage in entrepreneurial activity, opening an avant-garde cotton factory that employed almost five hundred people.

The English classical liberal philosopher Herbert Spencer also gives us a lesson in method, in character, and in industriousness. He accomplished an extraordinary, to say the least, amount of cultural work with uncommon perseverance and stubbornness, and made his living in the free market of culture with his successful articles and books, refusing the academic positions or offices that were offered to him.34

Closer to our days we can take the examples of Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich A. von Hayek, Murray N. Rothbard, Henry Hazlitt, and Bruno Leoni, all personalities who were respected and admired by those around them, who never sought positions of power, and who sometimes gave up important professional positions in order to remain consistent with their ideas. Refusing to adhere to the cultural fashions of the moment, they did not receive the recognition that they deserved, and that was commensurate with their intellectual greatness and personal integrity.

Intellectual, Moral, and Existential Misery

The Italian essayist Giovanni Birindelli has called socialists “stupid” because of their inability to understand the concept of spontaneous social order.35 It must be understood that this is not a gratuitous insult. Intelligence, in fact, has many faces: there is logical, mathematical, musical, emotional, social, etc. intelligence. Many socialists may be brilliant engineers, scientists, chess players, or artists, but they are decidedly obtuse in their understanding of social phenomena, which explains the thunderous and repeated failure of their ideas whenever they have been put into practice. The central idea of socialism, that a central planning authority can improve upon the conditions of society through its commands, prohibitions, and coercion, is indeed incredibly puerile and denotes a mind unprepared to grasp the complexity of social and economic phenomena. Society, in fact, is not a black box, and individuals are not motionless pieces on a chessboard that can be moved arbitrarily. Rather, as Jesús Huerta de Soto explains in treatise Socialism, Economic Calculation and Entrepreneurship, society is a dynamic structure, a highly complex process composed of human interactions which are motivated and kept together by the creative and coordinative force of unhampered entrepreneurs.36

Intellectual misery manifests itself first and foremost in the intellectual errors, ideological delusions, and complete lack of common sense that characterize much of the socialist literature. The biographies of the masters of left-wing thought show, with few exceptions, that there is less of a distance between thinking badly and behaving badly than we think, because poverty of thought is often accompanied by moral and existential poverty.

The moral misery of many left-wing intellectuals manifests itself in verbal ferocity, exhortations to violence, demonization of opponents, and lack of respect for the dignity of individuals. It is no coincidence that in the last 150 years, as noted by George Watson, all those who have theorized or advocated the extermination of peoples or social groups have called themselves “socialists.” No exception to this rule can be found.37

Moral misery is frequently linked to existential misery, which expresses itself in pathological egocentricity, vanity, the frenzied desire to always be in the limelight by espousing all the cultural fashions of the moment, servility, opportunism, parasitism toward one’s neighbors, the inconsistency between lofty proclamations, and crude or evil actions.

The revolutionary intellectual has no title to boast of any personal superiority nor to set himself up as the master of society. On the contrary, with his rambling ideologies and his bad human example, which has corrupted the minds and behavior of millions of young people, the revolutionary intellectual is undoubtedly the most pernicious figure of our times.

1. David Hume, A proposito di Rousseau, ed. Lorenzo Infantino (Soveria Mannelli, Italy: Rubbettino, 2017).

2. Paul Johnson, Intellectuals (New York: Harper and Row, 1989).

3. Cited in Roger D. Masters, The Political Philosophy of Rousseau (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 218.

4. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on Political Economy” and “The Social Contract,” trans. Christopher Betts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 45.

5. Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Society (New York: Basic Books, 2010), pp. 130–31.

6. Roger Scruton, A Short History of Modern Philosophy, 2d ed. (London: Routledge, 1995), p. 201.

7. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 10.

8. Tibor Fischer, The Thought Gang (1994; repr., London: Vintage Books, 2009), p. 124.

9. Gerard Casey, Freedom’s Progress? A History of Political Thought (Exeter: Imprint Academic, 2017), p. 505.

10. Johnson, Intellectuals, pp. 21–22.

11. Quoted in Gary North, “The Marx Nobody Knows,” in Requiem for Marx, ed. Yuri Maltsev (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1993), p. 107.

12. Quoted in Richard M. Ebeling, “Marx the Man,” Foundation for Economic Education, Feb. 14, 2017.

13. Nathaniel Weyl, Karl Marx: Racist (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1979).

14. Nathaniel Weyl, Karl Marx: Racist, pp. 24–72. Engels, of course, was not immune to Marx’s racism. For example, upon learning about the candidacy of Paul Lafargue—Marx’s son-in-law, who had some black blood in his veins—for the Municipal Council of the Fifth Arrondissment, a district which included the Paris Zoo, he wrote that Lafargue “is undoubtedly the most appropriate representative of that district” being “in his quality as a nigger a degree nearer to the rest of the animal kingdom than the rest of us.” Quoted in Saul Padover, Karl Marx, an Intimate Biography (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978), p. 502.

15. “The Negroes indulge … that perfect contempt for humanity, which in its bearing on Justice and Morality is the fundamental characteristic of the race…. The undervaluing of humanity among them reaches an incredible degree of intensity … want of self-control distinguished the character of the Negroes. This condition is capable of no development or culture, and as we see them at this day, such have they always been … Africa … is no historical part of the World; it has no movement or development to exhibit. Historical movements in it … belong to the Asiatic or European World…. What we properly understand by Africa, is the Unhistorical, Undeveloped Spirit, still involved in the conditions of mere nature, and which had to be presented here only as on the threshold of the World’s History.” George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of History (1837; repr., Kitchner, ON: Batoche Books, 2001), pp. 113–17.

16. Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847; repr., Charleston: Nabu Press, 2010), pp. 74–75.

17. John Lee Anderson, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (New York: Grove Press, 1997), p. 468.

18. Quoted in José E. Urioste Palomeque, “A Murderer Called “CHE,” Yucatan Times, Mar. 7, 2019.

19. Quoted in Alvaro Vargas Llosa, “The Killing Machine: Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand,” Independent Institute, July 11, 2005.

20. Quoted in Vargas Llosa, “The Killing Machine.”

21. Leonardo Facco, Che Guevara il comunista sanguinario: La storia sconosciuta del mitologico mercenario argentino (Bologna: Tramedoro, 2020), p. 64.

22. Quoted in Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 180.

23. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 194.

24. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 187.

25. Quoted in Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 245.

26. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 235.

27. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevalier (1949; repr., New York, Vintage, 2011).

28. While embarking on his return trip from the Soviet Union, for instance, Shaw, neglecting all the atrocities that were being committed in the name of socialism, described the USSR as “a land of hope.” Quoted in Paul Hollander, Political Pilgrims: Western Intellectuals in Search of the Good Society (1981; repr., New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2009), pp. 38–39.

29. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 245.

30. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 246.

31. Johnson, Intellectuals, p. 251.

32. Murray N. Rothbard, Keynes, the Man (Auburn, AL, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2010), p. 56.

33. Quoted in Evelyn L. Forget, The Social Economics of Jean-Baptiste Say: Markets and Virtue (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 262–63.

34. For a survey of Spencer’s life and work, see Guglielmo Piombini, “Herbert Spencer, un uomo contro lo Stato,” Miglioverde, Oct. 20, 2016.

35. Giovanni Birindelli, Legge e mercato (Treviglio, Italy: Leonardo Facco Editore, 2017).

36. In particular, see Jesús Huerta de Soto, Socialism, Economic Calculation and Entrepreneurship, trans. Melinda Stroup (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2010), p. 52.

37. George Watson, The Lost Literature of Socialism (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 1989).