Are entrepreneurs made or are they born? With entrepreneurial studies programs popping up at universities around the country one would assume they can be made, like doctors or architects. The reality is the primary quality of an entrepreneur can’t be taught: the stomach to risk everything and keep wanting more.

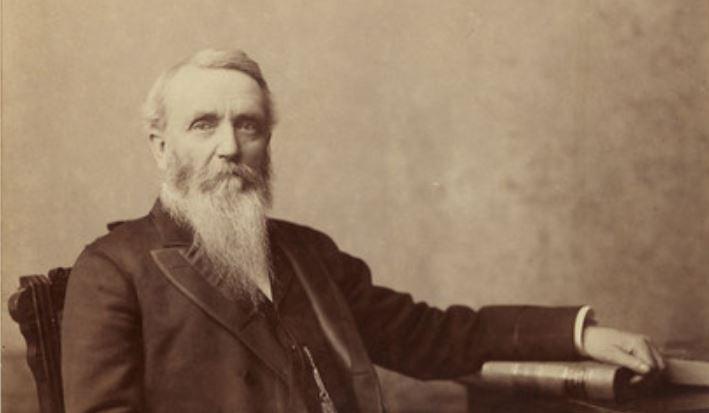

George Hearst was a true entrepreneur. Growing up in Missouri, he realized mining was more lucrative than farming and, as Matthew Bernstein writes in George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age, “he gambled away his easy life as a Missouri slaver and landowner for a chance at California gold.”

But Hearst was far from done with his success, and failures, in the California goldfields. He believed he had been late to the California rush, and when he received word of what would become the Comstock Lode he headed for Virginia City (today in Nevada), to prospect for silver. He would make another fortune.

For the first half of Bernstein’s very readable, and richly footnoted, book, Hearst was either bankrupt or rich; there was no in-between. He made and lost fortunes, but nothing slowed him down. He had a natural nose for finding gold and silver. Even after marrying Phoebe, who bore him a son, Willy, who went by W.R. as he grew older and whom the world came to know as William Randolph, the elder Hearst was rarely home. He was constantly looking for the next big score.

Along the way Hearst bought millions of acres of ranch land throughout the west and in Mexico and raised hundreds of thousands of head of cattle. While his bread and butter was mining, Hearst’s Achilles’ heels were San Francisco real estate, stock market speculation, and politics. But, he had five thousand men on his payroll and his family lived extravagantly. “[T]hey simply couldn’t go broke,” Bernstein writes.

With a life spanning 1820 to 1891, Hearst would meet and become friends with the likes of Mark Twain in Virginia City and barely miss the shootout at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone involving the Earp Brothers, Doc Holliday, and Curly Bill Brocius. Wild Bill Hickok would be shot at a card table in Deadwood just before Hearst arrived and ultimately made millions from the Homestake Mine. Ambrose Bierce would eventually be on his payroll at the San Francisco Examiner.

Fans of the HBO series Deadwood will recognize the author’s mention of Gem Saloon owner Al Swearengen, Calamity Jane, and Seth Bulloch. Bernstein mentions the series and Gerald McRaney’s portrayal of Hearst as a sociopath. The author believes it is too harsh. Lawyers fought his battles, not gunmen.

Hearst was no boy scout. He was accused of bribing jurors during his murder trial in Deadwood, there was the Great Mining suit in Pioche, and he bribed his way onto the US Senate. “Emblematic of the Gilded Age, Hearst was pathologically competitive,” Bernstein writes.

Hearst shut down the Homestake Mine in a bit of jiggery pokery to give the false impression it was a bust and then personally researched and found the original demarcations of the mine. Bernstein emphasizes, “Hearst demonstrated for good and all that in the great game of paydirt, he was second to none.”

It was politics that exposed Hearst’s lack of education and cultivation. The Los Angeles Times called him “Brainless George Hearst,” “an old ignormous, as unlettered as the backside of a tombstone” and an “illiterate Money Bags.”

Bernstein‘s sources include a number of letters from Phoebe and W.R. to George, but also newspapers from the period that seemed to report on any and all of Hearst’s comings and goings. The Pioche Daily Record is cited often. Located 180 miles northeast of Las Vegas, Pioche was a booming silver town. But the last census in 2010 had the town’s population at just over one thousand and there is no daily paper these days. The Daily Record was only published from 1872 to 1876.

Mark, the proprietor of the mining newsletter IKN Weekly, writes, “Aside from agriculture, there’s no other sector of industry that has created more true wealth for human society than the mining industry and the simple act of taking some of the earth’s crust, processing and selling the product for a profit is the very essence of Capitalism.”

To illustrate, there are passages in Bernstein’s book that would make a geologist’s heart stop. For instance, describing the Anaconda copper mine near Butte, Montana, “Hearst hired a mill and continued sinking. Thirty feet later they struck a bed of pure copper. Continuing to delve, they found that the bed was thirty to forty feet wide and descended more than a thousand feet. In other words, it was the greatest copper strike on the planet.” Pure implies 100 percent copper. These days miners are hoping to drill holes containing 1 percent copper.

Ludwig von Mises wrote in Human Action, “In order to succeed in business a man does not need a degree from a school of business administration. These schools train the subalterns for routine jobs. They certainly do not train entrepreneurs. An entrepreneur cannot be trained. A man becomes an entrepreneur by seizing an opportunity and filling the gap. No special education is required for such a display of keen judgment, foresight, and energy.”

George Hearst was exactly who Mises was describing.