Governments can pay their bills in three ways: taxes, debt, and inflation. The public usually recognizes the first two, for they are difficult to hide. But the third tends to go unnoticed by the public because it involves a slow and subtle reduction in the value of money, a policy usually unarticulated and complex in design.

In this article, I will look under the hood of the Federal Reserve during World War I to explain the actual tools and levers used by monetary authorities to reduce the value of the public’s money in order to fund government war spending. This example will help readers better understand the more general idea of an “inflation tax,” and how such a tax might be used in the future to fund the state’s wars.

It is the government’s monopoly over the money supply that allows it to resort to inflation as a form of raising revenue. Kings and queens, by secretly reducing the amount of gold in coins they issued to the public, could use the gold held back to pay for their own pet conquests. Slowly the public would discover that the coins they were using had less gold than the amount indicated on their face. Their value would be bid down, and the coin-holding public would bear the costs in lost purchasing power.

Legal-tender laws adopted by governments prevented the public from exchanging bad coins at less than their face value. A fall in market value, after all, would cut off a significant future revenue source: the government’s ability to issue bad coins at inflated values.

The use of force to subsidize an inferior coin’s value reduced its capacity to provide the holder with certainty, corrupted the informational value of the prices it provided, and diminished the public’s trust in the money. This decline in a monetary system’s efficacy due to bad money and legal-tender laws is always a cost born by the money-using public.

Just as kings debased coins to help pay for their wars, the Federal Reserve used inflation to help pay for US participation in World War I. It did so by creating and issuing dollars in return for government debt. In effect, the Fed’s balance sheet became a repository for war bonds. Furthermore, the Fed brought this debt onto its balance sheet at a higher price than the market would have paid otherwise, a subsidy borne by all those who held money as its purchasing power declined.

Before explaining how this process worked, it is necessary to know a few things about the Fed. The institution began operations in 1914 on the “real-bills” principle. Member banks could borrow cash from the Fed, but only by submitting “real bills” as collateral.

These bills were short-term debt instruments that were created by commercial organizations to help fund their continuing operations. The bills were in turn backed by business inventories, the “real” in real bills. By discounting or lending cash to banks on real bills, the Fed could increase the money supply.

The original Section 16 of the Federal Reserve Act required that all circulating notes issued by the central bank be backed 100% by real bills. On top of this, an additional 40% gold reserve was to be held by the Fed. In those days, Federal Reserve notes—a liability of the Fed—were convertible into gold, and the 40% gold reserve added additional security. Thus, for each dollar liability it issued, the Fed held 140% assets in its vaults, or one dollar in real bills and 40¢ in gold on the asset side of its balance sheet.

The Fed was also permitted to engage in open-market purchases of government debt and banker’s acceptances. But government debt was not of a commercial nature, and therefore was not considered a real bill. Because the 100% “real”-backing requirement for notes could not be satisfied by Fed holdings of government debt, the Fed could only issue a limited number of notes for government debt before running up against the 100% requirement.

Thus, the real-bills doctrine as set out in the Federal Reserve Act significantly hemmed off the Fed’s balance sheet from serving as a bin for the accumulation of government debt and claims to government debt. To help finance the war, which it had entered into in April 1917, the US government would have to open up the Fed’s balance sheet to the Treasury’s war debt.

A major step was taken in June 1917 with the relaxation of the double requirement of 100% real bills and 40% gold for each dollar issued. A small change to Section 16 now meant that the 40% gold reserve could simultaneously substitute for 40% of the real-bills requirement.

Rather than holding $1.40 in assets for each $1.00 issued ($1.00 real bills, 40¢ gold), the Fed now only needed to hold $1.00, comprised of 40¢ gold and 60¢ real bills. This freed up a significant amount of the Fed’s collateral for new issues of notes.

An earlier step to harness the Fed for war-financing purposes was the 1916 addition of Section 13.8 to the Federal Reserve Act. This change allowed the Fed for the first time to make loans to member banks with government debt serving as collateral. But such collateral was not considered a real bill, and therefore was not eligible to contribute to the 100% “real” backing requirement for dollars issued.

Thus, while loans on government debt were now permitted, their quantity was significantly limited. Only if there was some “slack” comprised of excess Fed holdings of real bills backing the note issue could 13.8 loans be made.

With the United States gearing up for the war, President Woodrow Wilson announced in April 1917 the first war-bond issues, or “Liberty-bond” drives. To help prop up the war-bond market, another change was made to the [Federal Reserve] Act to further pry open the Fed’s balance sheet to the acceptance of government debt. Section 13.8 loans were now permitted to serve along with real bills and gold as eligible backing assets for Federal Reserve notes.

Thus, the 60% “real”-backing requirement could be satisfied not only by real bills, but also “nonreal” government debt. The Fed now faced no constraints in bringing government debt onto its balance sheet to expand the note issue.

The ability to lend on the security of government debt was further strengthened by the Fed’s adoption of a preferential discount rate on all Section 13.8 loans secured by Liberty bonds. This rate was set at 3%, a full percent below the regular discount rate.

According to [P.H.] Fishe,1 member banks could make a profit on the spread by buying 3.5% Liberty bonds at government-debt auctions, then funding these purchases by submitting the bonds to the Fed as collateral for loans at the preferential rate of 3%. “If member banks subscribed to the entire Liberty bond issue by this method…they stood to gain $410,958 tax-free every fifteen days,” writes Fishe.

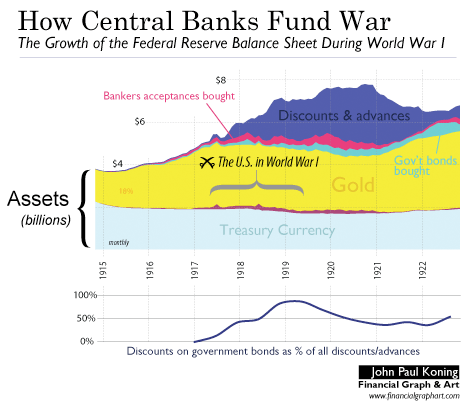

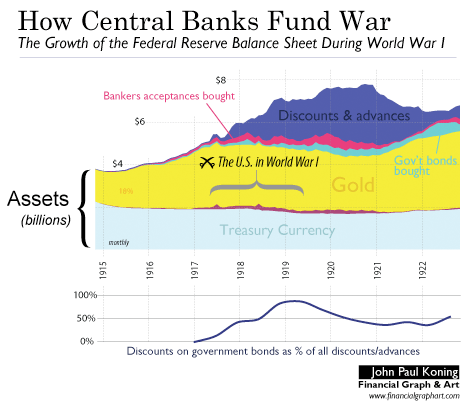

The immediate result of these changes was a massive increase in the Fed’s balance sheet, driven almost entirely by Fed loans to member banks secured by government debt. This is best observed in our chart above. The discounts/advances component of Federal Reserve assets (in blue) quickly expanded in 1917. By 1919, discounts collateralized by government debt had grown to almost 100% of all discounts made (line on bottom of chart). Collateral submitted prior to the changes had been primarily private debt.

The modifications that freed up the Fed’s collateral requirements now allowed the Fed’s balance sheet to act as a very effective “sink” for the accumulation of government war debt. No longer need the Treasury depend on the wherewithal of private individuals and banks to bring government debt onto their own balance sheets—they now had the central bank’s balance sheet to count on.

Furthermore, by overvaluing government debt collateral through the preferential discount rate, the Fed created an incentive system that encouraged the private sector to utilize the Fed as a “sink.” Private investors could acquire Liberty bonds, then submit them for cut-price discount loans.

The US Treasury was happy with this setup, as it meant that Liberty-bond drives would be met with significant demand from investors. The necessity of luring investors away from competing private-sector bond issuers by posting high rates was avoided. Now the Treasury could skirt the competition by using the Fed to provide subsidized loans through the preferential rate.

The result of all these machinations was a significant inflation, which varied between 13% and 20% for most of the war, up from the 1% inflation rate experienced in the Fed’s first year. By 1920 a dollar would buy about half the goods it was capable of purchasing in 1914.

To sum up, by overvaluing government debt, the Fed was able to issue money at a faster rate than it would otherwise have been capable of. The private sector, lured by the dangling carrot of an easy discount policy, went to the Fed for cash, but the sector had no real long-term demand for these dollars and tried to offload them, resulting in a fall in the dollar’s value.

At the same time, by overvaluing the government collateral it brought onto its balance sheet, the Fed reduced the quality of its own assets. Bankers and investors who watched such statistics grew wary and sold dollars for more credit-worthy stores of value.

In this way a portion of war costs were paid for by everyone who held the weakening dollar. Indeed, [Milton] Friedman and [Anna] Schwartz estimate that 5% of the cost of the war was funded by Fed inflation.2

With the Fed’s balance sheet widened to accept loans on government debt, the state’s ability to fund wars via inflation has been ensured. Independent central banking, established in the 1950s, has only gone part way in reducing the Treasury Department’s ability to use the Fed to subsidize wars. Only by completely removing the Federal Reserve’s monopoly over the money supply and introducing choice and competition in currency will this unfortunate link ever be fully severed.

Originally published November 2009.

- 1. P.H. Fishe, “The Federal Reserve Amendments of 1917: The Beginning of a Seasonal Note Issue Policy,”Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking (August 1991).

- 2. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963).