In January, money supply growth hit a new all-time high, rising slightly above September 2020’s previous high, and remaining well above growth levels that one year ago would have been considered unthinkable. January’s surge in money-supply growth makes January the tenth month in a row of remarkably high growth, and came in the wake of unprecedented quantitative easing, central bank asset purchases, and various stimulus packages.

Historically, the growth rate has never been higher than what we’ve seen over the past ten months, with the 1970s being the only period that comes close.

It is likely that growth will continue for the time being as it appears that now the United States is several months into an extended economic crisis, with around 1 million new jobless claims each week from March until mid-September. Claims have remained above 700,000 every week since. Moreover, more than 4.8 million unemployed workers are currently collecting standard unemployment benefits, and total unemployment claims have failed to fall back to non-recessionary levels, even a year after lockdowns began. More than seven million additional unemployed are collecting “Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation” as of March 4.

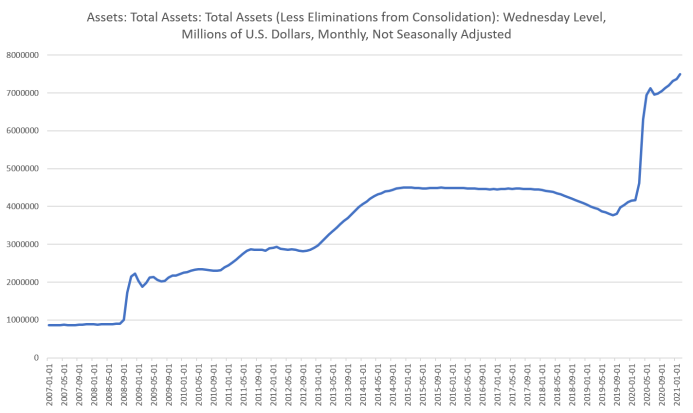

The central bank continues to engage in a wide variety of unprecedented efforts to “stimulate” the economy and provide income to unemployed workers and to provide liquidity to financial institutions. Moreover, as government revenues have fallen, Congress has turned to unprecedented amounts of borrowing. But in order to keep interest rates low, the Fed has been buying up trillions of dollars in assets—including government debt. This has fueled new money creation.

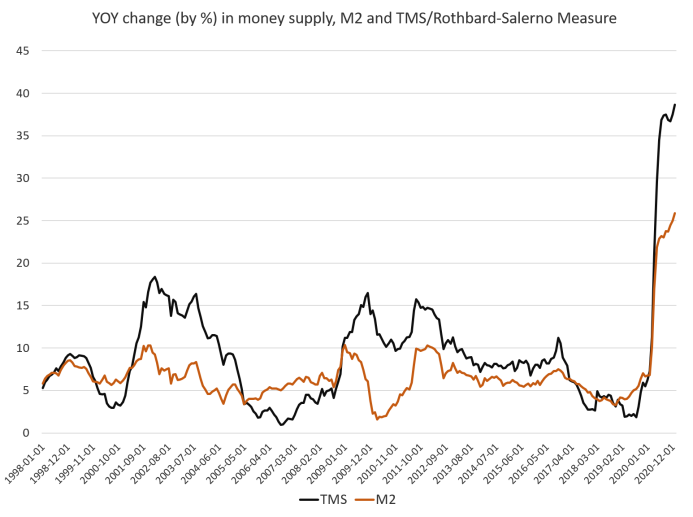

During January 2021, year-over-year (YOY) growth in the money supply was at 38.6 percent. That’s up slightly from December’s rate of 37.5 percent, and up from the January 2020 rate of 6.2 percent. Historically this is a very large surge in growth, year over year. It is also quite a reversal from the trend that only just ended in August of 2019 when growth rates were nearly bottoming out around 2 percent. In August 2019, the growth rate hit a 120-month low, falling to the lowest growth rates we’ve seen since 2007.

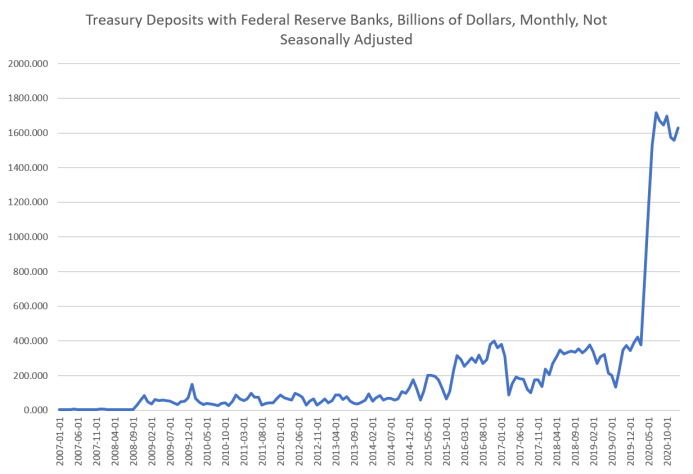

The money supply metric used here—the “true” or Rothbard-Salerno money supply measure (TMS)—is the metric developed by Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno, and is designed to provide a better measure of money supply fluctuations than M2. The Mises Institute now offers regular updates on this metric and its growth. This measure of the money supply differs from M2 in that it includes Treasury deposits at the Fed (and excludes short-time deposits, traveler’s checks, and retail money funds).

Similar to the TMS measure, the M2 growth rate reached new historic highs in January, growing 25.8 percent compared to December’s growth rate of 24.9 percent. M2 grew 6.7 percent during January of last year. The M2 growth rate had fallen considerably from late 2016 to late 2018 but has been growing again in recent months.

Money supply growth can often be a helpful measure of economic activity. During periods of economic boom, money supply tends to grow quickly as commercial banks make more loans. Recessions, on the other hand, tend to be preceded by periods of slowdown in rates of money supply growth. However, money supply growth tends to grow out of its low-growth trough well before the onset of recession. As recession nears, the TMS growth rate typically climbs and becomes larger than the M2 growth rate. This occurred in the early months of the 2002 and the 2009 crises. February 2020 was the first month since late 2008 that the TMS growth rate climbed higher than the M2 growth rate. The TMS growth rate exceeded M2 through most of 2020. As the year progresses, it does appear that the decline in money supply growth has again preceded a recession, and a severe one at that. The second, third, and fourth quarters of 2020 all showed negative growth in real GDP. Real GDP was down 9 percent, year over year, during the second quarter, and real GDP was down 2.4 percent, year over year, during the fourth quarter.

Government stimulus efforts have failed to turn economic growth positive.

After initial balance sheet growth in late 2019, total Fed assets surged to nearly $7.2 trillion in June and have rarely dipped below the $7 trillion mark since then. As of February, total assets have hit a new all-time high of over $7.5 trillion. These new asset purchases are propelling the Fed balance sheet far beyond anything seen during the Great Recession’s stimulus packages. The Fed’s assets are now up more than 600 percent from the period immediately preceding the 2008 financial crisis.

While Fed asset purchases are not solely responsible for the surge in new money creation, they are certainly a sizable factor. Bank loan activity has surged as well, also driving new money creation. Total Fed assets, going back to 2007:

Also of note is the continuing surge in the Treasury’s deposits at the Fed. There is some debate over why this amount has surged so much, and why the Treasury has decided to keep such a large amount of money at the Fed. The Fed certainly has contributed to this by buying bonds on the secondary market and keeping the US government very liquid. In any case, these deposits are counted as part of the money supply under the Rothbard-Salerno money-supply calculation. (It is not money according to M2.) But of course these deposits should be counted as money because recent stimulus packages have made it clear that the Federal government, could in fact spend hundreds of billions of dollars in a short period of time through various bailouts, stimulus checks and other measures. In other words, these deposits are very liquid. So, Treasury may just be keeping dollars on hand for the next spending spree.