Introduction by Joseph T. Salerno

Friedrich A. Hayek was only thirty-two years old when he published this two-part article in Economica, at the time, the world’s leading English-language economics journal. The article is a review essay of John Maynard Keynes’s two-volume book, A Treatise on Money, published the previous year. Keynes, a generation senior to Hayek, was at the time the leading economist of the British Cambridge School and had already achieved world renown as a public intellectual. Keynes worked hard and long on his treatise, having written the first page six years before it was published. Keynes clearly intended the work to be his magnum opus, a dazzling leap forward in the theory of money based on “a novel means of approach to the fundamental problems of monetary theory.”

But Keynes’s reach was much, much longer than his grasp given his parochial and stunted training in economic theory—one course in economics and the study of Alfred Marshall’s clunky and disjointed textbook. Keynes’s Treatise never stood a chance. For the brilliant and courageous young Hayek was waiting, having already fully absorbed and integrated in his own work Mises’s monetary and business cycle theories, Böhm-Bawerkian-Wicksellian capital theory, and the general analytical approach of the broad Austrian school from Menger onward that maintained an unwavering focus on the interrelationship among all economic phenomena.

Hayek’s article is a positive thrill to read. Hayek relentlessly scrutinizes and exposes the weak and patchwork structure of Keynes’s theoretical arguments and then dismantles it brick by brick, leaving nothing standing. Keynes’s reaction reveals just how deeply Hayek’s review cut as well as Keynes’s cavalier attitude toward intellectual pursuits. Keynes’s reply to the first part of Hayek’s article, which dealt with the first, purely theoretical volume of the Treatise, was not properly a reply at all but a critique of Hayek’s book Prices and Production. Upon publication six months later of the second part of Hayek’s article, which focused on the second, applied volume of the Treatise and in which Hayek was a bit more complimentary, Keynes remarked to Hayek, “Oh never mind, I no longer believe all that.”

Yet Keynes was not done. A month later, Keynes, as chief editor of the Economic Journal published a nasty review of Hayek’s Prices and Production written by one of Keynes’s more uncomprehending and rabid disciples, Piero Sraffa. Keynes’s fellow Cambridge economist, Arthur C. Pigou, was aghast at this behavior. Without naming names, Pigou wrote, “A year or two ago, after the publication of an important book, there appeared an elaborate and careful critique of a number of passages in it. The author’s answer was, not to rebut the criticism, but to attack with violence another book, which the critic had himself written several years before. Body-line bowling. The methods of the duello. That kind of thing is surely a mistake.”

Keynes’s response to his painstaking review of the Treatise was very discouraging for Hayek. In later years, Hayek often said that the reason he did not undertake a similar review of Keynes’s later and more influential General Theory was because Keynes so easily changed his mind and that he could not be sure that Keynes would have not done so again, once more rendering Hayek’s efforts for naught. Whether a scholarly review by Hayek of such a shrewdly designed tract for the times like the General Theory would have altered the course of economic theory and policy is problematic in any case.

The article you are about to read demonstrates that Hayek was a formidable economic disputant even at a relatively young age. But it also signifies a broader point about Hayek’s early work that has been sorely neglected by the continuing outpouring of works from the cottage industry of Hayek commentators, interpreters, and biographers. Hayek’s amazing burst of creativity from the late 1920s through the late 1930s was a product of his participation in the great theoretical controversies of the time. His opponents were some of the great (and not so great) figures in interwar economics: Keynes, W.T. Foster and W. Catchings, Ralph Hawtrey, Irving Fisher, Frank Knight, Josef Schumpeter, Gustav Cassel, Alvin Hansen, A.C. Pigou, Arthur Spiethoff to name a few.

Perhaps the greatest economic controversialist of the twentieth century by the age of forty, Hayek took on all comers without fear or favor and in a series of brilliant books and articles, notably Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, Prices and Production, Monetary Nationalism and International Stability, “The Paradox of Saving,” “The Mythology of Capital,” and the present article he had synthesized and elaborated the first positive statement of modern Austrian “macroeconomics.”

<!–

[Part One of this article was first published in Economica, No. 33. (Aug., 1931), pp. 270-295. Part Two was first published in Economica, No. 35. (Feb., 1932), pp. 22-44.]

–>

I. Introduction

The appearance of any work by Mr. J.M. Keynes must always be a matter of importance: and the publication of the Treatise on Money1 has long been awaited with intense interest by all economists. Nonetheless, in the event, the Treatise proves to be so obviously—and, I think, admittedly—the expression of a transitory phase in a process of rapid intellectual development that its appearance cannot be said to have that definitive significance which at one time was expected of it. Indeed, so strongly does it bear the marks of the effect of the recent discovery of certain lines of thought hitherto unfamiliar to the school to which Mr. Keynes belongs, that it would be decidedly unfair to regard it as anything else but experimental—a first attempt to amalgamate those new ideas with the monetary teaching traditional in Cambridge and pervading Mr. Keynes’s own earlier contributions. That the new approach, which Mr. Keynes has adopted, which makes the rate of interest and its relation to saving and investing the central problem of monetary theory, is an enormous advance on this earlier position, and that it directs the attention to what is really essential, seems to me to be beyond doubt. And even if, to a Continental economist, this way of approach does not seem so novel as it does to the author, it must be admitted that he has made a more ambitious attempt to carry the analysis into the details and complications of the problem than any that has been attempted hitherto. Whether he has been successful here, whether he has not been seriously hampered by the fact that he has not devoted the same amount of effort to understanding those fundamental theorems of “real” economics on which alone any monetary explanation can be successfully built, as he has to subsidiary embellishments, are questions which will have to be examined later.

That such a book is theoretically stimulating goes without saying. At the same time, it is difficult to suppress some concern as regards the immediate effect which its publication in its present form may have on the development of monetary theory. It was, no doubt, the urgency which he attributes to the practical proposals which he holds to be justified by his theoretical reasoning, which led Mr. Keynes to publish the work in what is avowedly an unfinished state. The proposals are indeed revolutionary, and cannot fail to attract the widest attention: they come from a writer who has established an almost unique and well-deserved reputation for courage and practical insight; they are expounded in passages in which the author displays all his astonishing qualities of learning, erudition and realistic knowledge, and in which every possible effort is made to verify the theoretical reasoning by reference to available statistical data. Moreover, most of the practical conclusions seem to harmonize with what seems to the man in the street to be the dictates of common sense, and the favorable impression thus created will probably not be diminished at all by the fact that they are based on a part of the work (Books III and IV) which is so highly technical and complicated that it must forever remain entirely unintelligible to those who are not experts. But it is this part on which everything else depends. It is here that all the force and all the weakness of the argument are concentrated, and it is here that the really original work is set forth. And here, unfortunately, the exposition is so difficult, unsystematic, and obscure, that it is extremely difficult for the fellow economist who disagrees with the conclusions to demonstrate the exact point of disagreement and to state his objections. There are passages in which the inconsistent use of terms produces a degree of obscurity which, to anyone acquainted with Mr. Keynes’s earlier work, is almost unbelievable. It is only with extreme caution and the greatest reserve that one can attempt to criticize, because one can never be sure whether one has understood Mr. Keynes aright.

For this reason, I propose in these reflections to neglect for the present the applications, which fill almost the whole of Volume II, and to concentrate entirely on the imperative task of examining these central difficulties. I address myself expressly to expert readers who have read the book in its entirety.2

II. Keynes’s History of Monetary Theory

Book I gives a description and classification of the different kinds of money which in many respects is excellent. Where it gives rise to doubts or objections, the points of difference are not of sufficient consequence to make it necessary to give them space which will be much more urgently needed later on. The most interesting and important parts consist in the analysis of the factors which determine the amounts of money which are held by different members of the community, and the division of the total money in circulation into “income deposits” and “business deposits” according to the purpose for which it is held. This distinction, by the way, has turned up again and again in writings on money since the time of Adam Smith (whom Mr. Keynes quotes), but so far it has not proved of much value.

Book II is a highly interesting digression into the problem of the measurement of the value of money, and forms in itself a systematic and excellent treatise on that controversial subject. Here it must be sufficient to say that it deals with the problem in the most up-to-date manner, treating index-numbers on the lines developed chiefly by Dr. Haberler in his Sinn der Indexzahlen, as expressions of the changes in the price-sum of definite collections of commodities—its main addition to the existing knowledge of this subject being an excellent and very much needed criticism of certain attempts to base the method of index numbers on the theory of probability. For an understanding of what follows, I need only mention that Mr. Keynes distinguishes as relatively less important for the purposes of monetary theory the Currency Standard in its two forms, the Cash Transactions Standard and the Cash Balances Standard (and the infinite number of possible secondary price levels corresponding, not to the general purchasing power of money as a whole, but to its purchasing power for special purposes), from the “Labor Power” of Money and the Purchasing Power of Money proper, which are fundamental in a sense in which price levels based on other types of expenditure are not, because “human effort and human consumption are the ultimate matters from which alone economic transactions are capable of deriving any significance” (Vol. I, p. 134).

III. Keynes’s Analysis of Profit

It is in Books III and IV that Mr. Keynes proposes “a novel means of approach to the fundamental problem of monetary theory” (Preface). He begins with an elaborate catalogue of the terms and concepts he wants to use. And here, right at the beginning, we encounter a peculiarity which is likely to prove a stumbling block to most readers, the concept of entrepreneur’s profits. These are expressly excluded from the category of money income, and form a separate category of their own. I have no fundamental objection to this somewhat irritating distinction, and I agree perfectly when he defines profits by saying that “when profits are positive (or negative) entrepreneurs will—in so far as their freedom of action is not fettered by existing bargains with the factors of production which are for the time being irrevocable—seek to expand (or curtail) their scale of operations” and hence depicts profits as the mainspring of change in the existing economic system. But I cannot agree with his explanation of why profits arise, nor with his implication that only changes in “total profits” in his sense can lead to an expansion or curtailment of output. For profits in his view are considered as a “purely monetary phenomenon” in the narrowest sense of that expression. The cause of the emergence of those profits which are “the mainspring of change” is not a “real” factor, not some maladjustment in the relative demand for and supply of cost goods and their respective products (i.e., of the relative supply of intermediate products in the successive stages of production) and, therefore, something which could arise also in a barter economy, but simply and solely spontaneous changes in the quantity and direction of the flow of money. Indeed, throughout the whole of his argument the flow of money is treated as if it were the only independent variable which could cause a positive or negative difference between the prices of the products and their respective costs. The structure of goods on which this flow impinges is assumed to be relatively rigid. In fact, of course, the original cause may just as well be a change in the relative supply of these classes of goods, which then, in turn, will affect the quantities of money expended on them.3

But though many readers will feel that Mr. Keynes’s analysis of profit leaves out essential things, it is not at all easy to detect the flaw in his argument. His explanation seems to flow necessarily from the truism that profits can arise only if more money is received from the sale of goods than has been expended on their production. But, obvious as this is, the conclusion drawn from it becomes a fallacy if only the prices of finished consumption goods and the prices paid for the factors of production are contrasted. And, with the quite insufficient exception of new investment goods, this is exactly what Mr. Keynes does. As I shall repeatedly have occasion to point out, he treats the process of the current output of consumption goods as an integral whole in which only the prices obtained at the end for the final products and the prices paid at the beginning for the factors of production have any bearing on its profitableness. He seems to think that sufficient account of any change in the relative supply (and therefore in the value) of intermediate products in the successive stages of that process is provided for by his concept of (positive or negative) investment, i.e., the net addition to (or diminution from) the capital of the community. But this is by no means sufficient if only the total or net increment (or decrement) of investment goods in all stages is considered and treated as a whole, and the possibility of fluctuations between these stages is neglected; yet this is just what Mr. Keynes does. The fact that his whole concept of investment is ambiguous, and that its meaning is constantly shifting between the idea of any surplus beyond the reproduction of the identical capital goods which have been used up in current production and the idea of any addition to the total value of the capital goods, renders it still less adequate to account for that phenomenon.

When I come to the concept of investment I shall quote evidence of this confusion. For the present, however, let us assume that the concept of investment includes, as, in spite of some clearly contradictory statements of Mr. Keynes it probably should include, only the net addition to the value of all the existing capital goods. If we take a situation where, according to that criterion, no investment takes place, and therefore the total expenditure on the factors of production is to be counted as being directed towards the current production of consumers’ goods, it is quite conceivable that—to take an extreme case—there may be no net difference between the total receipts for the output and the total payments for the factors of production, and no net profits for the entrepreneurs as a whole, because profits in the lower stages of production are exactly compensated by the losses in the higher stages. Yet, in that case, it will not be profitable for a time for entrepreneurs as a whole to continue to employ the same quantity of factors of production as before. We need only consider the quite conceivable case that in each of the successive stages of production there are more intermediate products than are needed for the reproduction of the intermediate products existing at the same moment in the following stage, so that, in the lower stages (i.e., those nearer consumption) there is a shortage, and in the higher stages there is an abundance, as compared with the current demand for consumers’ goods. In this case, all the entrepreneurs in the higher stages of production will probably make losses; but even if these losses were exactly compensated, or more than compensated, by the profits made in the lower stages, in a large part of the complete process necessary for the continuous supply of consumption goods it will not pay to employ all the factors of production available. And while the losses of the producers of those stages are balanced by the profits of those finishing consumption goods, the diminution of their demand for the factors of production cannot be made up by the increased demand from the latter because these need mainly semi-finished goods and can use labor only in proportion to the quantities of such goods which are available in the respective stages. In such a case, profits and losses are originally not the effect of a discrepancy between the receipts for consumption goods and the expenditure on the factors of production, and therefore they are not explained by Mr. Keynes’s analysis. Or, rather, there are no total profits in Mr. Keynes’s sense in this case, and yet there occur those very effects which he regards as only conceivable as the consequence of the emergence of net total profits or losses. The explanation of this is that while the definition of profits which I have quoted before serves very well when it is applied to individual profits, it becomes misleading when it is applied to entrepreneurs as a whole. The entrepreneurs making profits need not necessarily employ more original factors of production to expand their production, but may draw mainly on the existing stocks of intermediate products of the preceding stages while entrepreneurs suffering losses dismiss workmen.

But this is not all. Not only is it possible for the changes which Mr. Keynes attributes only to changes in “total profits”) to occur when “total profits” in his sense are absent: it is also possible for “total profits” to emerge for causes other than those contemplated in his analysis. It is by no means necessary for “total profits” to be the effect of a difference between current receipts and current expenditure. Nor need every difference between current receipts and current expenditure lead to the emergence of “total profits.” For even if there is neither positive nor negative investment, yet entrepreneurs may gain or lose in the aggregate because of changes in the value of capital which existed before—changes due to new additions to or subtractions from existing capital.4 It is such changes in the value of existing intermediate products (or “investment,” or capital, or whatever one likes to call it) which act as a balancing factor between current receipts and current expenditure. Or to put the same thing another way, profits cannot be explained as the difference between expenditure in one period and receipts in the same period or a period of equal length because the result of the expenditure in one period will very often have to be sold in a period which is either longer or shorter than the first period. It is indeed the essential characteristic of positive or negative investment that this must be the case.

It is not possible at this stage to show that a divergence between current expenditure and current receipts will always tend to cause changes in the value of existing capital which are by no means constituted by that difference, and that because of this, the effects of a difference between current receipts and current expenditure (i.e., profits in Mr. Keynes’s sense), may lead to a change in the value of existing capital which may more than balance the money profits. We shall have to deal with this matter in detail when we come to Mr. Keynes’s explanation of the trade cycle, but before we can do that, we shall have to analyze his concept of investment very closely. It should, however, already be clear that even if his concept of investment does not refer, as has been assumed, to changes in the value of existing capital but to changes in the physical quantities of capital goods—and there can be no doubt that in many parts of his book Mr. Keynes uses it in this sense—this would not remedy the deficiencies of his analysis. At the same time there can be no doubt that it is the lack of a clear concept of investment—and of capital—which is the cause of this unsatisfactory account of profits.

There are other very mischievous peculiarities of this concept of profits which may be noted at this point. The derivation of profits from the difference between receipts for the total output and the expenditure on the factors of production implies that there exists some normal rate of remuneration of invested capital which is more stable than profits. Mr. Keynes does not explicitly state this, but he includes the remuneration of invested capital in his more comprehensive concept of the “money rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production” in general, a concept on which I shall have more to say later on. But even if it be true, as it probably is, that the rate of remuneration of the original factors of production is relatively more rigid than profits, it is certainly not true in regard to the remuneration of invested capital. Mr. Keynes obviously arrives at this view by an artificial separation of the function of the entrepreneurs as owners of capital and their function as entrepreneurs in the narrow sense. But these two functions cannot be absolutely separated even in theory, because the essential function of the entrepreneurs, that of assuming risks, necessarily implies the ownership of capital. Moreover, any new chance to make entrepreneurs’ profits is identical with a change in the opportunities to invest capital, and will always be reflected in the earnings (and value) of capital invested. (For similar reasons it seems to me also impossible to mark off entrepreneurs’ profits as something fundamentally different from, say, the extra gain of a workman who moves first to a place where a scarcity of labor makes itself felt and, therefore, for some time obtains wages higher than the normal rate.)

Now this artificial separation of entrepreneurs’ profits from the earnings of existing capital has very serious consequences for the further analysis of investment: it leads not to an explanation of the changes in the demand price offered by the entrepreneurs for new capital, but only to an explanation of changes in their aggregate demand for “factors of production” in general. But, surely, an explanation of the causes which make investment more or less attractive should form the basis of any analysis of investment. Such an explanation can, however, only be reached by a close analysis of the factors determining the relative prices of capital goods in the different successive stages of production—for the difference between these prices is the only source of interest. But this is excluded from the outset if only total profits are made the aim of the investigation. Mr. Keynes’s aggregates conceal the most fundamental mechanisms of change.

IV. Keynesian Confusion on Investment

I pass now to the central and most obscure theme of the book, the description and explanation of the processes of investment. It seems to me that most of the difficulties which arise here are a consequence of the peculiar method of approach adopted by Mr. Keynes, who, from the outset, analyses complex dynamic processes without laying the necessary foundations by adequate static analysis of the fundamental process. Not only does he fail to concern himself with the conditions which must be given to secure the continuation of the existing capitalistic (i.e., roundabout) organization of production—the conditions creating an equilibrium between the depreciation and the renewal of existing capital—not only does he take the maintenance of the existing capital stock more or less as a matter of course (which it certainly is not—it requires quite definite relationships between the prices of consumption goods and the prices of capital goods to make it profitable to keep capital intact): he does not even explain the conditions of equilibrium at any given rate of saving, nor the effects of any change in the rate of saving. Only when money comes in as a disturbing factor by making the rate at which additional capital goods are produced different from the rate at which saving is taking place does he begin to be interested.

All this would do no harm if his analysis of this complicating moment were based on a clear and definite theory of capital and saving developed elsewhere, either by himself or by others. But this is obviously not the case. Moreover, he makes a satisfactory analysis of the whole process of investment still more difficult for himself by another peculiarity of his analysis, namely by completely separating the process of the reproduction of the old capital from the addition of new capital, and treating the former simply as a part of current production of consumption goods, in defiance of the obvious fact that the production of the same goods, whether they are destined for the replacement of or as additions to the old stock of capital, must be determined by the same set of conditions. New savings and new investment are treated as if they were something entirely different from the reinvestment of the quota of amortization of old capital, and as if it were not the same market where the prices of capital goods needed for the current production of consumption goods and of additional capital goods are determined. Instead of a “horizontal” division between capital goods (or goods of higher stages or orders) and consumption goods (or goods of lower stages)—which one would have thought would have recommended itself on the ground that in each of these groups and sub-groups production will be regulated by similar conditions—Mr. Keynes attempts a kind of vertical division, counting that part of the production of capital goods which is necessary for the continuation of the current production of consumption goods as a part of the process of producing consumption goods, and only that part of the production of capital goods which adds to the existing stock of capital as production of investment goods. But this procedure involves him, as we shall see, in serious difficulties when he has to determine what is to be considered as additional capital—difficulties which he has not clearly solved. The question is whether any increase of the value of the existing capital is to be considered as such an addition-in this case, of course, such an addition could be brought about without any new production of such goods—or whether only additions to the physical quantities of capital goods are counted as such an addition—a method of computation which becomes clearly impossible when the old capital goods are not replaced by goods of exactly the same kind, but when a transition to more capitalistic methods brings it about that other goods are produced in place of those used up in production.

This continual attempt to elucidate special complications without first providing a sufficient basis in the form of an explanation of the more simple equilibrium relations becomes particularly noticeable in a later stage of the investigation when Mr. Keynes tries to incorporate into his system the ideas of Wicksell. In Wicksell’s system these are necessary outgrowths of the most elaborate theory of capital we possess, that of Böhm-Bawerk. It is a priori unlikely that an attempt to utilize the conclusions drawn from a certain theory without accepting that theory itself should be successful. But, in the case of an author of Mr. Keynes’s intellectual caliber, the attempt produces results which are truly remarkable.

Mr. Keynes ignores completely the general theoretical basis of Wicksell’s theory. But, nonetheless, he seems to have felt that such a theoretical basis is wanting, and accordingly he has sat down to work one out for himself. But for all this, it still seems to him somewhat out of place in a treatise on money, so instead of presenting his theory of capital here, in the forefront of his exposition, where it would have figured to most advantage, he relegates it to a position in Volume II and apologizes for inserting it (Vol. 11, p. 95). But the most remarkable feature of these chapters (27–29) is not that he supplies at least a part of the required theoretical foundation, but that he discovers anew certain essential elements of Böhm-Bawerk’s theory of capital, especially what he calls (as has been done before in many discussions of Böhm-Bawerk’s theory—I mention only Taussig’s Wages and Capital as one of the earliest and best known instances) the “true wages fund” (Vol. 11, pp. 127–129) and earlier (Vol. I, p. 308) Böhm-Bawerk’s formula for the relation between the average length of the roundabout process of production and the amount of capital.5 Would not Mr. Keynes have made his task easier if he had not only accepted one of the descendants of Böhm-Bawerk’s theory, but had also made himself acquainted with the substance of that theory itself?

V. The Process of Investment

We must now consider in more detail Mr. Keynes’s analysis of the process of investment. Not the least difficult part of this task is to find out what is really meant by the expression investment as it is used here. It is certainly no accident that the inconsistencies of terminology, to which I have alluded before, become particularly frequent as soon as investment is referred to. I must mention here some of the most disturbing instances, as they will illustrate the difficulties in which every serious student of Mr. Keynes’s book finds himself involved.

Perhaps the clearest expression of what Mr. Keynes thinks when he uses the term investment is to be found where he defines it as “the act of the entrepreneur whose function it is to make the decisions which determine the amount of the non-available output” consisting “in the positive act of starting or maintaining some process of production or of withholding liquid goods. It is measured by the net addition to wealth whether in the form of fixed capital, working capital or liquid capital” (Vol. I, p. 172).

It is perhaps somewhat misleading to use the term investment for the act as well as the result, and it might have been more appropriate to use in the former sense the term “investing.” But that would not matter if Mr. Keynes would confine himself to these two senses, for it would not be difficult to keep them apart. But while the expression “net addition to wealth” in the passage just quoted clearly indicates that investment means the increment of the value of existing capital—since wealth cannot be measured otherwise than as value—somewhat earlier, when the term “value of investment” occurs for the first time (Vol. I, p. 126), it is expressly defined as “not the increment of value of the total capital, but the value of the increment of capital during any period.” Now, in any case, this would be difficult as, if it is not assumed that the old capital is always replaced by goods of exactly the same kind so that it can be measured as a physical magnitude, it is impossible to see how the increment of capital can be determined otherwise than as an increment of the value of the total. But, to make the confusion complete, side by side with these two definitions of investment as the increment of the value of existing capital and the value of the increment, four pages after the passage just quoted, he defines the “Value of the Investment” (should the capital V or the second “the” explain the different definition?) not as an increment at all but as the “value of the aggregate of Real and Loan Capital” and contrasts it with the increment of investment which he now defines as “the net increase of the items belonging to the various categories which make up the aggregate of Real and Loan Capital” while “the value of the increment of investment” is now “the sum of the values of the additional items.”

These obscurities are not a matter of minor importance. It is because he has allowed them to arise that Mr. Keynes fails to realize the necessity of dealing with the all-important problem of changes in the value of existing capital; and this failure, as we have already seen, is the main cause of his unsatisfactory treatment of profit. It is also partly responsible for the deficiencies of his concept of capital. I have tried hard to discover what Mr. Keynes means by investment by examining the use he makes of it, but all in vain. It might be hoped to get a clearer definition by exclusion from the way in which he defines the “current output of consumption goods” for, as we shall see later, the amount of investment stands in a definite relation to the current output of consumers’ goods so that their aggregate cost is equal to the total money income of the community. But here the obscurities which obstruct the way are as great as elsewhere. While on page 135, the cost of production of the current output of consumption goods is defined as total earnings minus that part of it which has been earned by the production of investment goods (which a few pages earlier (p. 130) has been defined as “non-available output plus the increment of hoards”), there occurs on page 130 a definition of the “output of consumption goods during any period” as “the flow of available output plus the increment of Working Capital which will emerge as available output,” i.e., as including part of the as yet non-available output which, in the passage quoted before, has been included in investment goods and therefore excluded from the current output of consumption goods. And still a few pages earlier (Vol. I, p. 127) a “flow of consumers’ goods” appears as part of the available output, while on the same page “the excess of the flow of increment to unfinished goods in process over the flow of finished goods emerging from the productive prices” (which, obviously, includes “the increment of Working Capital which will emerge as available output” which, in the passage quoted before, is part of the output of consumption goods) is now classed as non-available output. I am afraid it is not altogether my fault if at times I feel altogether helpless in this jungle of differing definitions.

VI. A Picture of the Process Itself

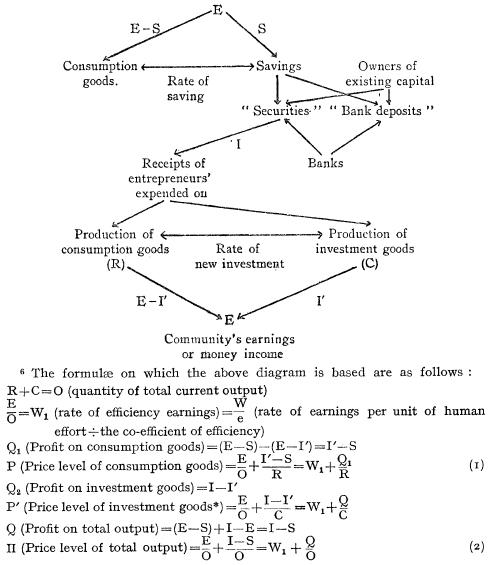

In the preceding sections we have made the acquaintance of the fundamental concepts which Mr. Keynes uses as tools in his analysis of the process of the circulation of money. Now we must turn to his picture of the process itself. The skeleton of his exposition is given in a few pages (Vol. I, pp. 135–40) in a series of algebraic equations which, however, are not only very difficult, but can only be correctly understood in connection with the whole of Book III. In the adjoining diagram, I have made an attempt to give a synoptic view of the process as Mr. Keynes depicts it, which I hope will give an adequate idea of the essential elements of his exposition.

Diagrammatic Version of Mr. Keynes’s Theory of the Circulation of Money

Community’s Earnings Or Money Income

(The numbers in brackets denote Mr. Keynes’s first and second fundamental equations respectively.)

There is a disturbing lack of method in Mr. Keynes’s choice of symbols, which makes it particularly difficult to follow his algebra. The reader should especially remember that while profits on the production of consumption goods, investment goods, and total profits are denoted by Q1, Q2, and Q respectively, the symbols for the corresponding price levels are chosen without any parallelism as P, P’, and II. On the other hand, there is a misleading parallelism between P and P’ and I and I’, where the dash does not stand for a similar relation, but in the former case serves to mark off the price level of investment goods from that of consumption goods, and in the second case to distinguish the cost of production of the increment of new investment goods (I’) from its value (I).

* This formula is not given by Mr. Keynes.

E, which stands at the top and again at the bottom of the diagram, represents (according to the definition which opens Book III) the total earnings of the factors of production. These are to be considered as identically one and the same thing as (a) the community’s money income (which includes all wages in the widest sense of the word, the normal remuneration of the entrepreneurs, interest on capital, regular monopoly gains, rents and the like) and (b) “the cost of production.” Though the definition does not expressly say so, the use Mr. Keynes makes of the symbol E clearly shows that that “cost of production” refers to current output. But here the first difficulty arises. Is it necessarily true that the E, which was the cost of production of current output, is the same thing as the E which is earned during the period when this current output comes on to the market and which therefore is available to buy that current output? If we take the picture as a crosscut at any moment of time, there can be no doubt that the E at the top and the E at the bottom of our diagram, i.e., income available for the purchase of output and the earnings of the factors of production, will be identical, but that does not prove that the cost of current output need necessarily also be the same. Only if the picture were to be considered as representing the process in time as a kind of longitudinal section, and if then the two E’s at the top and at the bottom (i.e., current money income and the remuneration of the factors of production which were earned from the production of current output) were still equal, would the assumption made by Mr. Keynes be actually given. But this could only be true in a stationary state: and it is exactly for the analysis of a dynamic society that Mr. Keynes constructs his formulae. And in a dynamic society that assumption does not apply.

But whatever the relations of earnings to the cost of production of current output may be, there can be no doubt that Mr. Keynes is right when he emphasizes the importance of the fact that the flow of the community’s earnings of money income shows “a twofold division (1) into the parts which have been earned by the production of consumption-goods and investment-goods respectively and (2) into parts which are expended on consumption goods and savings respectively” (Vol. I, p. 134) and that these two divisions need not be in the same proportion, and that any divergence between them will have important consequences.

Clearly recipients of income must make a choice: they may spend on consumption goods or they may refrain from doing so. In Mr. Keynes’s terminology the latter operation constitutes saving. Insofar as they do save in this sense, they have the further choice between what one would ordinarily call hoarding and investing or, as Mr. Keynes (because he has employed these more familiar terms for other concepts) chooses to call it, between “bank-deposits” and “securities.”6 Insofar as the money saved is converted into “loan or real capital,” i.e., is lent to entrepreneurs or used to buy investment goods, this means a choice for what Mr. Keynes calls “securities” while when it is held as money this means a choice for “bank deposits.” This choice, however, is not only open to persons saving currently, but also to persons who have saved before and are therefore owners of the whole block of old capital. But even this is not yet the end. There is a third and most important factor which may affect the relation between what is currently saved and what becomes currently available for the purposes of investment: the banks. If the demand of the public for bank deposits increases either because the people who save invest only part of the amounts saved, or because the owners of old capital want to convert part of their “securities” into “bank deposits,” the banks may create the additional deposits and use them to buy the “securities” which the public is less anxious to hold, and so make up for the difference between current saving and the buying of securities. The banking system may, of course, also create deposits to a greater or a lesser extent than would be necessary for this purpose and will then itself be one of the three factors causing the divergence between savings and investment in “securities.”

On the other hand, entrepreneurs will receive money from two sources: either from the sale of the output of consumption goods, or from the “sale” of “securities” (which means investment in the ordinary sense), which latter operation may take the form of selling investment goods they have produced or raising a loan for the purpose of holding old or producing new investment goods. I understand—I am not sure whether Mr. Keynes really intends to convey this impression—that the total received from these two sources will be equal to the value of new investment, but in this case it would be identical with the amount of the “securities,” and there would then be no reason to introduce this latter term. If, however, I should be mistaken on that point, the symbol I (which stands for the value of new investments) would not belong to the place where I have inserted it in the diagram above.

In regard to this total of money at the disposal of entrepreneurs, these have a further and, as must be conceded to Mr. Keynes, to a certain extent independent choice: they have to decide what part of it shall be used for the current production of consumption goods and what part for the production of new investment goods. But their choice is by no means an arbitrary one; and the way in which changes in the two variables mentioned above and changes in technical knowledge and the relative demand for different consumption goods (those which require more or less capital for their production) influence the relative attractiveness of the two lines is the most important problem of all, a problem which can be solved only on the basis of a complete theory of capital. And it is just here, though, of course, Mr. Keynes devotes much effort to the discussion of this central problem, that the lack of an adequate theoretical basis and the consequent obscurities of his concept of “investment,” which I have noted before, make themselves felt. The whole idea that it is possible to draw in the way he does a sharp line of distinction between the production of investment goods and the current production of consumption goods is misleading. The alternative is not between producing consumption goods or producing investment goods, but between producing investment goods which will yield consumption goods at a more or less distant date in the future.

The process of investment does not consist in producing side by side with what is necessary to continue current production of consumption goods on the old methods, additional investment goods, but rather in producing other machinery, for the same purpose but of a greater degree of efficiency, to take the place of the inferior machinery, etc., used up in the current production of consumption goods. And when the entrepreneurs decide to increase their investment, this does not necessarily mean that at that time more original factors of production than before are employed in the production of investment goods, but only that the new processes started will have the effect that, because of their longer duration, after some time a smaller proportion of the output will be “available” and a larger “non-available.” Nor does it mean as a matter of course that even that part of the total amount spent on the factors of production which is not new investment but only reproduction of capital used up in the current production of consumption goods, will become available after the usual time.

VII. Static Model of a Dynamic Process

But, in addition to all these obscurities which are a consequence of the ambiguity of the concept of investment employed by Mr. Keynes, and which, of course, disturb all the apparent neatness of his mathematical formulae, there is a further difficulty introduced with these formulae. In order to provide an explanation of the changes in the price level (or rather price levels) he needs, in addition to his symbols denoting amounts of money or money values, symbols representing the physical quantities of the goods on which the money is spent. He therefore chooses his units of quantities of goods in such a way that “a unit of each has the same cost of production at the base date” and calls O “the total output of goods in terms of these units in a unit of time, R the volume of liquid Consumption-goods and Services flowing onto the market and purchased by the consumers, and C the net increment of investment, in the sense that O=R+C” (Vol. I, p. 135). Now these sentences, which are all that is said in explanation of these important magnitudes, give rise to a good deal of doubt. Whatever “cost of production” in the first sentence means (I suppose it means money cost, in which case R would be identical with E–I’ and C with I’ at the base date), the fact that these units are based on a relation existing at an arbitrarily chosen base date makes them absolutely unsuitable for the explanation of any dynamic process. There can be no doubt that any change of the proportion between what Mr. Keynes calls production of consumption goods and what he calls production of investment goods will be connected with changes of the quantities of the goods of both types which can be produced with the expenditure of a given amount of costs. But if, as a consequence of such a change, the relative costs of consumption goods and investment goods change, this means that the measurement in units which are produced at equal cost at some base date is a measurement according to an entirely irrelevant criterion. It would be nonsense to consider as equivalent a certain number of bottles and an automatic machine for producing bottles because, before the fall in the rate of interest made the use of such a machine profitable, it cost as much to produce the one as the other. But this is exactly what Mr. Keynes would be compelled to do if he only stuck to his definitions. But, of course, he does not, as is shown by the fact that he treats (E/O)R as identical with E–I’ and (E/O)C as identical with I’ throughout periods of change—which would only be the case if his units of quantity were neither determined by equality of money cost at the base date (money cost without a fixed base would give no measure of quantities) nor, indeed, by any cost at the base date at all, but by some kind of variable “real cost.” This is probably what Mr. Keynes has in mind most of the time, though he never says so—but I cannot see how it will help him in the end. But not only does the division of O into its component parts R and C give rise to such difficulties. The use which is made of O alone is also not free from objections. We shall see in a moment that E/O (i.e., the total income divided by the total output) forms one of the terms of both his fundamental equations. Mr. Keynes calls this the “money rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production,” or more shortly the “money rate of efficiency earnings.” Now let me remind the reader for a moment that E means, as identically one and the same thing, (1) the community’s money income, (2) the earnings of the factors of production and (3) the cost of production, and that it expressly includes interest on capital and therefore in any case interest earned on existing capital goods.7 I must confess that I am absolutely unable to attach any useful meaning to his concept of “the money rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production” if capital is to be included among the factors of production and if it is ex hypothesi assumed that the amount of capital and therefore its productivity is changing. If the units in which O is measured are in any sense cost units, it is surely clear that interest will not stand in the same relation to the cost of production of the capital goods as the remuneration of the other factors of production to their cost of production? Or does there lie at the basis of the concept some attempt to construct a common denominator of real cost so as to include “abstinence”?

Mr. Keynes shows a certain inclination to identify efficiency earnings with efficiency wages (as when he speaks about the prevailing type of contracts between entrepreneurs and the factors of production being that of efficiency-earnings rather than effort-earnings—what does efficiency-earnings or even effort-earnings mean in regard to capital?—or when he speaks about the rate of earnings per unit of human effort (cf. Vol. I, pp. 135, 153, 166 et seq.), and in regard to wages the concept of efficiency earnings certainly has some sense if it is identified, as it is on page 166, with piece wages. But even if we assume that all contracts with labor were on the basis of piece wages, it would by no means follow that so long as existing contracts continue, efficiency wages would always be E/O. Piece rates relate only to a single workman or perhaps a group of workmen and their respective immediate output, but never to output as a whole. If, at unchanged piece rates for the individual workmen, total output rises as a consequence of an improved organization of the total process of production, E/O may change (because O is increased) without any corresponding change in the rate of money earnings of the individuals. A type of contract according to which the earnings of factors engaged in the higher stages of production automatically changed as their contribution to the output of the last stage changed not only does not exist, it is inconceivable. There is, therefore, no market where the “money rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production” is determined, and no price or group of prices which would correspond to that concept. What it amounts to is, as Mr. Keynes himself states in several places (e.g. Vol. I, p. 136), nothing else but the average cost of production of some more or less arbitrarily chosen units of output (i.e., such units as had “equal costs at the base date”) which will change with every change of the price of the units of the factors of production (including interest) as well as with every change in the organization of production, and therefore with every change not only in the average price of the factors of production, but also with every change in their relative prices—changes which generally lead to a change in the methods of production and therefore in the amount of output produced with a given amount of factors of production. To call this the “money rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production” and occasionally even simply “rate of earnings” can have no other effect than to convey the misleading impression that this magnitude is determined solely by the existing contracts with the factors of production.

VIII. The Circulation of Money

Mr. Keynes’s picture of the circulation of money shows three points where spontaneous change may be initiated: (1) the rate of saving may change, i.e., the division of the total money income of the community into the parts which are spent on consumption goods and saving respectively; (2) the rate of investment may change, i.e., the proportion in which the factors of production are directed by entrepreneurs to the production of consumption goods and the production of additional investment goods respectively; (3) banks may pass on to investors more or less money than that part of the savings which is not directly invested (and that part of the old capital which is withdrawn from investment) but converted into bank deposits so that the total of money going to entrepreneurs as investment surpasses or falls short of total savings.

If only (1) changes, i.e., if the rate of saving changes without any corresponding change in (2) and (3) from the position existing before the change in (1) (which is to be taken as an equilibrium position) took place the effect will be that producers of consumption goods receive so much more or less for their output than has been expended on its production as E–S exceeds or falls short of E–1′. (E–S)–(E–I’) or I’–S, i.e., the difference between savings and the cost of investment, will be equal to the profits on the production of consumption goods; and as this magnitude is positive or negative entrepreneurs will be induced to expand or curtail output. Provided that (3) remains at the equilibrium position, i.e., that banks will pass on to the entrepreneurs exactly the amount which is saved and not invested directly, the effect on the production of investment goods will be exactly the reverse of the effect on the production of consumption goods. That is to say (positive or negative) profits made on the production of consumption goods will be exactly balanced by (negative or positive) profits on the production of investment goods. A change in (1) will, therefore, never give rise to total profits, but only to partial profits balanced by equal losses, and only lead to a shift between the production of consumption goods and the production of investment goods which will go on until profits on both sides disappear.

It is easily to be seen that the effect of changes of the type (2) will, if not accompanied by changes in either (1) or (3), be of exactly the same nature as of changes in (1). Positive profits on the one hand and negative profits on the other will soon show that the deviation from the equilibrium position existing before without a corresponding change in (1) is unprofitable and will lead to a re-establishment of the former proportion between the production of consumption goods and the production of investment goods.

Only a change in (3) will lead to total profits. (This is also shown by the formula for total profits, namely Q=I–S.) Now the causes why I may be different from S are of a very complex nature, and are investigated by Mr. Keynes in very great detail. We shall have to discuss his analysis of this problem when we come to his theory of the bank rate. For present purposes, it will, however, be more convenient to take the possibility of such a divergence for granted, and only to mention that the fact that more (or less) money is being invested than is being saved is equivalent to so much money being added to (or withdrawn from) industrial circulation, so that the total of profits, or the difference between the expenditure and the receipts of the entrepreneurs, which is the essential element in the second term of the fundamental equations, will be equal to the net addition to (or subtraction from) the effective circulation. It is here, according to Mr. Keynes, that we find the monetary causes working for a change in the price level; and he considers it the main advantage of his fundamental equations that they isolate this factor.

IX. Changes in the Price Level

The aim of the fundamental equations is to “exhibit the causal process, by which the price level is determined, and the method of transition from one position of equilibrium to another” (Vol. I, p. 135). What they say is essentially that the purchasing power of money (or the general price level) will deviate from its “equilibrium position,” i.e., the average cost of production of the unit of output, only if I’ or I (if the price level in general and not the purchasing power of money, or the price level of consumption goods is concerned) is different from S. This has to be constantly kept in mind lest the reader be misled by occasional statements which convey the impression that this applies to every change in the price level, and not only to changes relatively to cost of production8 or that the “equilibrium position” is in any way definitely determined by the existing contracts with the factors of production,9 and not simply the cost of production, or what means the same thing, the “money-rate of efficiency earnings of the factors of production.”

The best short explanation of the meaning of the fundamental equations I can find is the following:

Thus, the long period equilibrium norm of the Purchasing Power of Money is given by the money-rate of efficiency earnings of the Factors of Production; whilst the actual Purchasing Power oscillates below or above this equilibrium level according as the cost of current investment is running ahead of, or falling behind, savings…. A principal object of this Treatise is to show that we have here the clue to the way in which the fluctuations of the price level actually come to pass, whether they are due to oscillations about a steady equilibrium or to a transition from one equilibrium to another…. Accordingly, therefore, as the banking system is allowing the rate of investment to exceed or fall behind the rate of saving, the price level (assuming that there is no spontaneous change in the rate of efficiency-earnings) will rise or fall. If, however, the prevailing type of contract between the entrepreneurs and the factors of production is in terms of effort-earnings W and not in terms of efficiency-earnings W, (existing arrangements probably lie as a rule somewhere between the two) then it would be (I/E)P, which would tend to rise or fall, where, as before, e is the coefficient of efficiency. (Vol. I, pp. 152–3)

This says quite clearly that not all changes of the price level need to be started by a divergence between I’ (or I) and S, but that it is only one particular cause of such changes, i.e., the changes in the amount of money in circulation, which is isolated by this form of equation. But the peculiar substitution of the misleading term “the money-rate of efficiency earnings of the Factors of Production” for simply money cost of production seems at places to mislead Mr. Keynes himself. I cannot see any reason whatever why, as indicated in the passage just quoted, and elaborated at length in a later section (pp. 166–170) so long as the second term is in the equilibrium position, i.e., zero, the movement of the price level should be at all dependent upon the prevailing type of contract with the factors of production. So long as the amount of money in circulation, or more exactly E, remains unchanged, the fluctuations in the price level would by no means be determined by the existing contracts, but exclusively by the amount of factors of production available and changes in their efficiency, i.e., by the two factors affecting total output. All Mr. Keynes’s reasoning on this point seems to be based on the assumption that existing contracts will be changed by entrepreneurs only under the inducement (or pressure) of positive (or negative) profits created by a change in the second term. But to me there seems, on the contrary, no doubt possible that if a change in the coefficient of efficiency (or the amount of the factors of production available) occurs, existing contracts will have to be changed unless there is a change in the second term. The difference seems to lie in the fact that Mr. Keynes believes that it is possible to adapt the amount of money in circulation to what is necessary for the maintenance of existing contracts without upsetting the equilibrium between saving and investing.

But under the existing monetary organization, where all changes in the quantity of money in circulation are brought about by more or less money being lent to entrepreneurs than is being saved, any change in the circulation must be accompanied by a divergence between saving and investing. I cannot see why “if such spontaneous changes in the rate of earnings as tend to occur require a supply of money which is incompatible with the ideas of the Currency Authority or with the limitations on its powers, then the latter will be compelled, in its endeavour to redress the situation, to bring influences to bear which will upset the equilibrium of Investment and Saving, and so induce the entrepreneurs to modify their offers to the factors of production in such a way as to counteract the spontaneous changes which have been occurring in the rates of earnings” (Vol. I, p. 167). To me it seems rather that if the currency authority wished to adapt the supply of money to the changed requirements, it could do so only by upsetting the equilibrium between saving and investment. But Mr. Keynes later on expressly allows for such increases in the supply of money as correspond to the increase of output and regards them as not upsetting the equilibrium. But how can the money get into circulation without creating a discrepancy between saving and investment? Is there any justification for the assumption that under these conditions entrepreneurs will borrow more just to go on with current production and not use the additional money for new investment? And even if they do use it only to finance the increased production, does not even this mean new investment in the interval of time until the additional products reach the consumer?

It seems to me that by not clearly distinguishing between stable cost of production per unit of output, stable contracts with the factors of production, and stable total cost (i.e., an invariable E) Mr. Keynes is led to connect two things which have nothing to do with one another: on the one hand the maintenance of a price level which will cover costs of production while contracts with the factors of production are more or less rigid, and on the other hand the maintenance of an equilibrium between saving and investment. But without changes in the quantity of money and therefore without a divergence between I’ and S, not only the purchasing power of money, but also the labor power of money, and therefore contracts with the factors of production would have to change with every change in total output.

There can, of course, be no doubt that every divergence between I or I’ and S is of enormous importance. But that importance does not lie in the direction of its influence on the fluctuations of the price level, be it its absolute fluctuations or its fluctuations about an equilibrium position, determined by the existing contracts with the factors of production.

It is true that in this attempt to establish a direct connection between a divergence between I and S, or what amounts to the same thing, a divergence between the natural and the money rate of interest, and the changes in the price level, Mr. Keynes is following the lead of Wicksell. But it is just on this point that—as has been shown by Mr. D.H. Robertson10 among English economists, and by the present writer11 on the Continent—Wicksell has claimed too much for his theory. And even if Mr. Keynes substitutes for the absolute stability of the price level which Wicksell had in mind, a not clearly defined equilibrium price level, he is still searching for a more definite relation between the price level and the difference between saving and investment than can be found.

X. Explanatory Tools

So far we have been mainly concerned with the tools which Mr. Keynes has created for the explanation of dynamic processes and the trade cycle. It is intended to discuss his actual explanation, beginning with the theory of the bank rate and including the whole of Book IV, in a second part of this article.12

There is just one word more I feel I should add at this point. It is very likely that in the preceding pages I have quite often clothed my comments in the form of a criticism where I should simply have asked for further explanation and that I have dwelt too much on minor inaccuracies of expression. I hope it will not be considered a sign of inadequate appreciation of what is undeniably in so many ways a magnificent performance that what I have had so far to say was almost exclusively critical. My aim has been throughout to contribute to the understanding of this unusually difficult and important book, and I hope that my endeavor in this direction will be the best proof of how important I consider it. It is even possible that in the end it will turn out that there exists less difference between Mr. Keynes’s views and my own than I am at present inclined to assume. The difficulty may be only that Mr. Keynes has made it so extraordinarily hard really to follow his reasoning. I hope that the reviewer will be excused if, in a conscientious attempt to understand it, he may sometimes have been betrayed into impatience with the countless obstacles which the author has put in the way of a full understanding of his ideas.

XI. Keynes’s Theory of the Bank Rate

Towards the end of his summary of the argument contained in those sections of the Treatise which were discussed in the first part of this article, Mr. Keynes writes: “If the banking system controls the terms of credit in such a way that savings are equal to the value of new investment, then the average price level of output as a whole is stable and corresponds to the average rate of remuneration of the factors of production. If the terms of credit are easier than this equilibrium level, prices will rise, profits will be made…. And if the terms of credit are stiffer than the equilibrium level, prices will fall, losses will be made…. Booms or slumps are simply the expression of the results of an oscillation of the terms of credit about their equilibrium position.”13 This brings us to the first and, in many respects, the most important question we have to consider in this second article, viz. Mr. Keynes’s theory of the bank rate.

The fundamental concept, upon which his analysis of this subject is based, is Wicksell’s idea of a natural, or equilibrium, rate of interest, i.e., the rate at which the amount of new investment corresponds to the amount of current savings—a definition of Wicksell’s concept on which, probably, all his followers would agree. Indeed, when reading Mr. Keynes’s exposition, any student brought up on Wicksell’s teaching will find himself on what appears to be quite familiar ground until, his suspicions having been aroused by the conclusions, he discovers that, behind the verbal identity of the definition, there lurks (because of Mr. Keynes’s peculiar definition of saving and investment) a fundamental difference. For the meaning attached by Mr. Keynes to the terms “saving” and “investment” differs from that usually associated with them. Hence the rate of interest which will equilibrate “savings” and “investment” in Mr. Keynes’s sense is quite different from the rate which would keep them in equilibrium in the ordinary sense.

The most characteristic trait of Mr. Keynes’s explanation of a deviation of the actual short-term rate of interest from the “natural” or equilibrium rate is his insistence on the fact that this may happen independently of whether the effective quantity of money does, or does not, change. He emphasizes this point so strongly that he could scarcely expect any reader to overlook the fact that he wishes to demonstrate it. But, at the same time, while he certainly wants to establish this proposition, I cannot find any proof of it in the Treatise. Indeed, at all the critical points, the assumption seems to creep in that this divergence is made possible by the necessary change in the supply of money.14

It is quite certain that his reason for believing that a difference between saving and investment can arise without the banks changing their circulation does not become clear in the first section of the relevant chapter. In this section he distinguishes three different strands of thought in the traditional doctrine only the first and third of which are relevant to this point, so that the second, which is concerned with the effect of the bank rate on international capital movements, may be neglected here. According to Mr. Keynes, the first of these strands of thought “regards Bank Rate merely as a means of regulating the quantity of bank money” (p. 187) while the third strand “conceives of Bank Rate as influencing in some way the rate of investment and, perhaps, in the case of Wicksell and Cassel, as influencing the rate of investment relatively to that of saving” (p. 190). But, as Mr. Keynes himself sees in one place (p. 197), there is no necessary conflict between these two theories. The obvious relation between them, which would suggest itself to any reader of Wicksell—a view which was certainly held by Wicksell himself—is that since, under the existing monetary system, changes in the amount of money in circulation are brought about mainly by the banks expanding or contracting their loans, and since money so borrowed at interest is used mainly for purposes of investment, any addition to the supply of money, not offset by a reverse change in the velocity of circulation, is likely to cause a corresponding excess of investment over saving; and any decrease will cause a corresponding excess of saving over investment. But Mr. Keynes believes that Wicksell’s theory was something different from this and, in fact, rather like his own, apparently because Wicksell thought that one and the same rate of interest may serve both to make saving and investment equal and to keep the general price level steady. As I have already stated, however, this is a point on which, in my view, Wicksell was wrong. But there can be no doubt that Wicksell was emphatically of the opinion that the possibility of there being a divergence between the market rate and the equilibrium rate of interest is entirely due to the “elasticity of the monetary system” (see Geldzins und Güterpreise, p. 101, Vorlesungen, p. 221 of Vol. II) i.e., to the possibility of adding money to, or withdrawing it from, circulation.

XII. Lack of a Satisfactory Theory

Mr. Keynes’s own exposition of the General Theory of the Bank Rate (pp. 200–209) does not, by any means, solve the problem of how a divergence between the bank rate and the equilibrium rate should affect prices and production otherwise than by means of a change in the supply of money. Nowhere more than here is one conscious of the lack of a satisfactory theory as to the effects of a change in the equilibrium rate; and of the confusion which results from the fundamentally different treatment of fixed and working capital. In most parts of his analysis, one is not clear whether he is speaking of the effects of any change in the bank rate, or whether what he says applies only to the effect of the bank rate being different from the market rate; nowhere does he make it clear that a central bank is in a position to determine the rate only because it is in a position to increase or decrease the amount of money in circulation.

But the least satisfactory part of this section is the oversimplified account of how a change in bank rate affects investment or, rather, the value of fixed capital—since, for some unexplained reason, he here substitutes this latter concept for the former. This explanation consists merely in pointing out that, since “a change in Bank Rate is not calculated to have any effect (except, perhaps, a remote effect of the second order of magnitude) on the prospective yield of fixed capital” and since the conceivable effect on the price of that yield may be neglected, the only “immediate, direct and obvious effect” of a change in the bank rate on the value of fixed capital will be that its given yield will be capitalized at the new rate of interest (p. 202). But capitalization is not so directly an effect of the rate of interest; it would be truer to say that both are effects of one common cause, viz. the scarcity or abundance of means available for investment, relative to the demand for those means. Only by changing this relative scarcity will a change in the bank rate also change the demand price for the services of fixed capital. If a change in the bank rate corresponds to a change in the equilibrium rate it is only an expression of that relative scarcity which has come about independently of this action. But if it means a movement away from the equilibrium rate, it will become effective and influence the value of fixed capital only insofar as it brings about a change in the amount of funds available for investment.

It is not difficult to see why Mr. Keynes came to neglect this obvious fact. For it is scarcely possible to see how a change in the rate of interest operates at all if one neglects, as Mr. Keynes neglects in this connection, the part played by the circulating capital which cooperates with the fixed capital; only in this way can one see how a change in the amount of free capital will affect the value of invested capital. To overemphasize the distinction between fixed and circulating capital, which is, at best, merely one of degree, and not by any means of fundamental importance, is a common trait of English economic theory and has probably contributed more than any other cause to the unsatisfactory state of the English theory of capital at the present time. In connection with the present problem it is to be noted that his neglect of working capital not only prevents him from seeing in what way a change in the rate of interest affects the value of fixed capital, but also leads him to a quite erroneous statement about the degree and uniformity of that effect. It is simply not true to state that a change in the rate of interest will have no noticeable effect on the yield of fixed capital; this would be to ignore the effect of such a change on the distribution of circulating capital. The return attributable to any piece of fixed capital, any plant, machinery, etc., is, in the short run, essentially a residuum after operating costs are deducted from the price obtained for the output, and once a given amount has been irrevocably sunk in fixed capital, even the total output obtained with the help of that fixed capital will vary considerably, according to the amount of circulating capital which it pays at the given prices, to use in cooperation with the fixed capital. Any change in the rate of interest will, obviously, materially alter the relative profitableness of the employment of circulating capital in the different stages of production, according as an investment for a longer or shorter period is involved; so that it will always cause shifts in the use of that circulating capital between the different stages of production, and bring about changes in the marginal productivity (the “real yield”) of the fixed capital which cannot be so shifted. As the price of the complementary working capital changes, the yield and the price of fixed capital will, therefore, vary; and this variation may be different in the different stages of production. The change in the price of working capital, however, will be determined by the change in the total means available for investment in all kinds of capital goods (“intermediate products”), whether of durable or non-durable nature. Any increase of means available for such investment will necessarily tend to lower the marginal productivity of any further investment of capital, i.e., lower the margins of profit derived from the difference between the prices of the intermediate products and the final products by raising the prices of the former relatively to the prices of the latter.

It would appear that Mr. Keynes’s failure to see these interrelations is due to the fact that he does not clearly distinguish, in the passage referred to above, between the gross and the net yield of fixed capital. If he had concentrated on the effects of a change in the rate of interest on the net yield, as being the only relevant phenomenon, he could hardly have failed to see that the effect of such a change on fixed capital is not quite as direct and uniform as he supposes; and he would certainly have remembered also that there exists a tendency for the net money yield of real capital and the rate of interest to become equal. Thus, the process of capitalization at any given rate of interest means merely that, while money is obtainable at a rate of interest lower than the rate of yield on existing capital, borrowed money will be used to purchase capital goods until their price is so enhanced that the rate of yield is lowered to equal the rate of interest; and vice versa.

XIII. Keynes’s Peculiar Concept of Saving

Although these deficiencies account for the fact that Mr. Keynes has not seen what I think is the true effect of a divergence between bank rate and equilibrium rate of interest, their existence does not give an explanation of Mr. Keynes’s own solution to this problem. This has to be sought elsewhere, viz. as already indicated, in Mr. Keynes’s peculiar concept of saving. He believes that, in order to maintain equilibrium, new investment must be equal not only to that part of the money income of all individuals which exceeds what they spend on consumers’ goods plus what must be reinvested in order to maintain existing capital equipment (which would constitute saving in the ordinary sense of the word); but also to that portion of entrepreneurs’ “normal” incomes by which their actual income (and, therefore, their expenditure on consumption goods) has fallen short of that “normal” income. In other words, if entrepreneurs are experiencing losses (i.e., are earning less than the normal rate), and make up for such losses either by cutting down their own consumption pari passu, or by borrowing a corresponding amount from the savers, then, argues Mr. Keynes, not only do these sums make replacement of the old capital possible, but there should also be a further amount of new investment corresponding to these sums.15 And as Mr. Keynes obviously thinks that saving (i.e., the refraining from buying consumers’ goods) may, in many cases, actually cause some entrepreneurs to suffer losses which will absorb some of the savings which would otherwise have gone to new investment, this special concept of saving probably explains why he suspects almost any increase in saving of being conducive to the creation of a dangerous excess of saving over investment.